Family Ties to The U

CORAL GABLES, Fla. – The University of Miami Sports Hall of Fame (UMSHoF) features only three sets of immediate relatives among its elite group of 334 inductees.

Two of them are father/son duos who both played football at The U in Eddie Dunn and Gary Dunn, as well as George Mira Sr. and George Mira Jr.

The other pair is unique in multiple ways. It features a father and daughter, one who played baseball and one who coaches tennis.

Ernie Yaroshuk earned induction into the UMSHoF in 1992 and his daughter, Paige Yaroshuk-Tews, got her call in 2012.

“Our Hall of Fame, they usually get it right,” said Rick Remmert, Miami’ associate athletic director of alumni programs. “And, boy, did they ever nail it here in making Ernie and Paige their first father/daughter duo in the Hall.”

As a Miami native whose father starred for the Hurricanes, life for Paige growing up was largely centered on the Hurricanes.

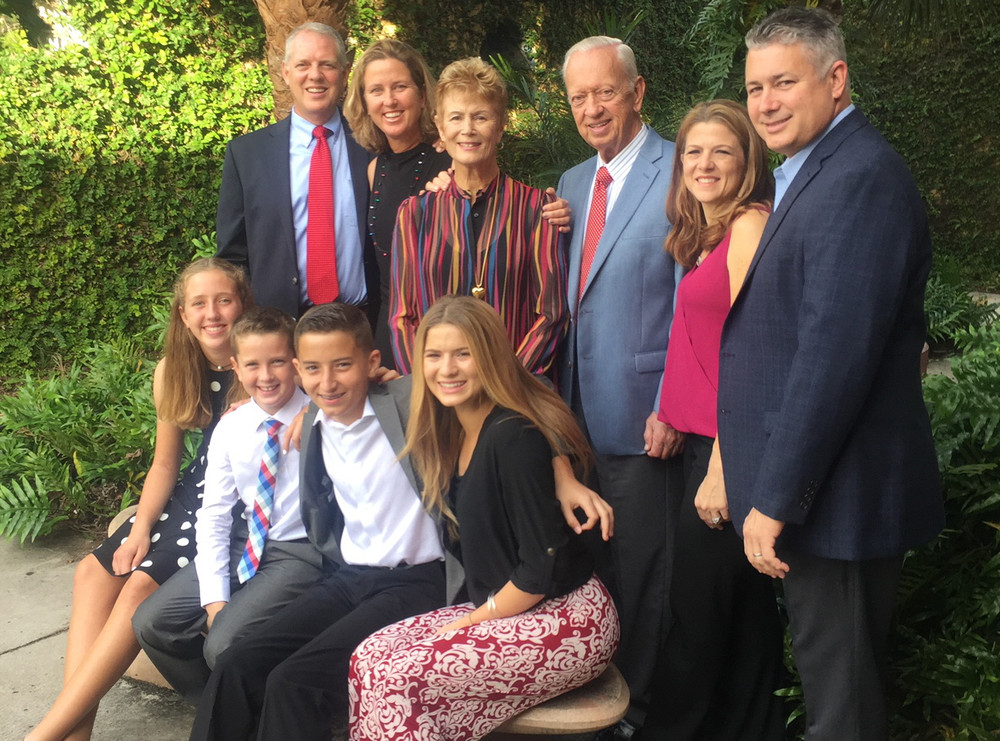

Her “best weekends” as a child were the ones spent with her family—including her mother, Carol, and older brother, Ernie Jr.—watching the Hurricanes compete on one field or another.

“It was our every weekend, going to the Orange Bowl. It was, during baseball, we looked forward to running around and chasing foul balls behind the bleachers at Mark Light,” Paige recalled. “Our entire schedule was kind of based around the University of Miami athletics, between baseball and football. We tailgated before every single football game. It was just kind of like, literally, part of our existence as a family. It was like our entertainment; Miami athletics was our entertainment. That’s what’s we did.”

The Yaroshuk family still attends Miami games together to this day.

(L to R: Carol, Ernie, Paige, Scott Tews, Ernie Jr.)

Paige would also go to the Neil Schiff Tennis Center to see Miami stars Lise Gregory and Ronni Reis, the 1986 NCAA doubles champions, in action.

On the days she went to Mark Light Field to watch the powerhouse Miami baseball program, her father would talk about the strategy of baseball. Paige and Ernie Jr., would listen to him pose questions about what they would do in certain spots, learning the intricacies of the game.

Ernie would also often talk about Ron Fraser, the legendary Hurricane coach who helped change the sport across the country.

The “Wizard of College Baseball,” as he is affectionately known, claimed two national titles at The U and remains synonymous with the program to this day, even after his passing in 2013.

“He had a respect for Ron Fraser that was just unbelievable,” Paige said of her father. “…So many of those games or many of those dinners before the games would be just talking about the type of man that Ron Fraser was. [He would tell us] how Ron Fraser treated him and how impactful coach Fraser was for him as a student-athlete, as a baseball player, as a person.”

Fraser’s tenure at Miami ended in 1992, the year Ernie earned his well-deserved enshrinement in the UMSHoF.

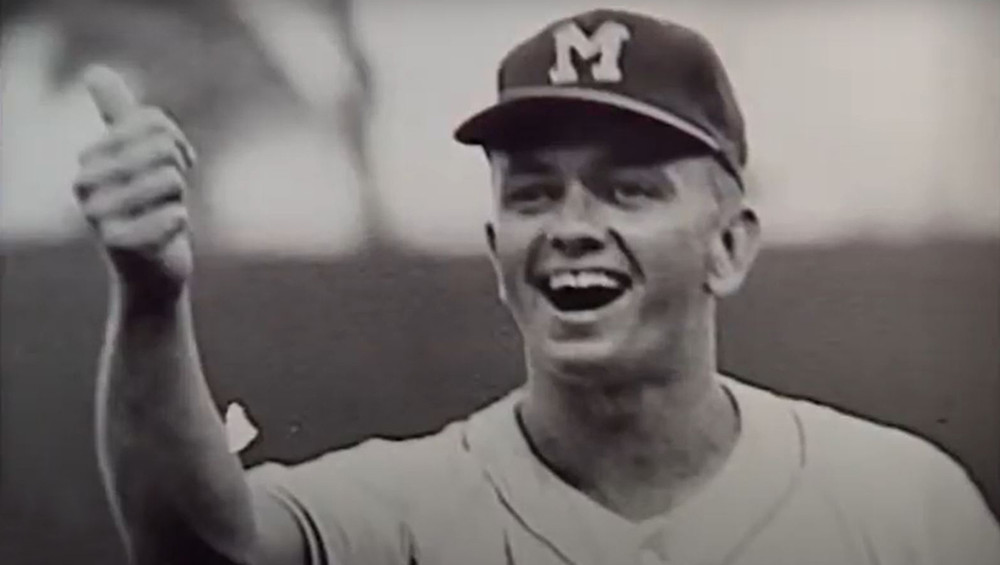

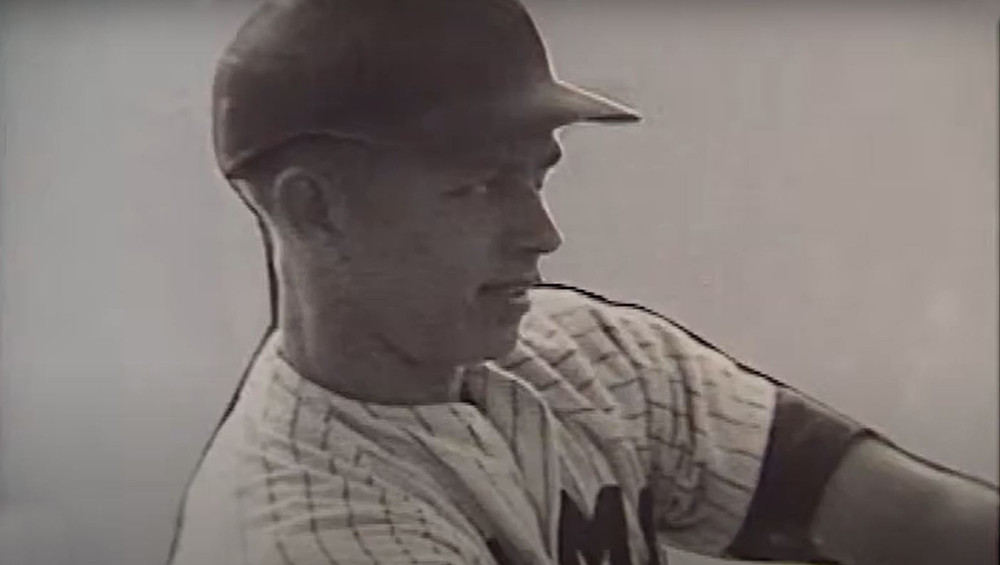

His 30-year run, meanwhile, started when Ernie was a senior in 1963 and was one of the few upperclassmen Fraser kept on the roster.

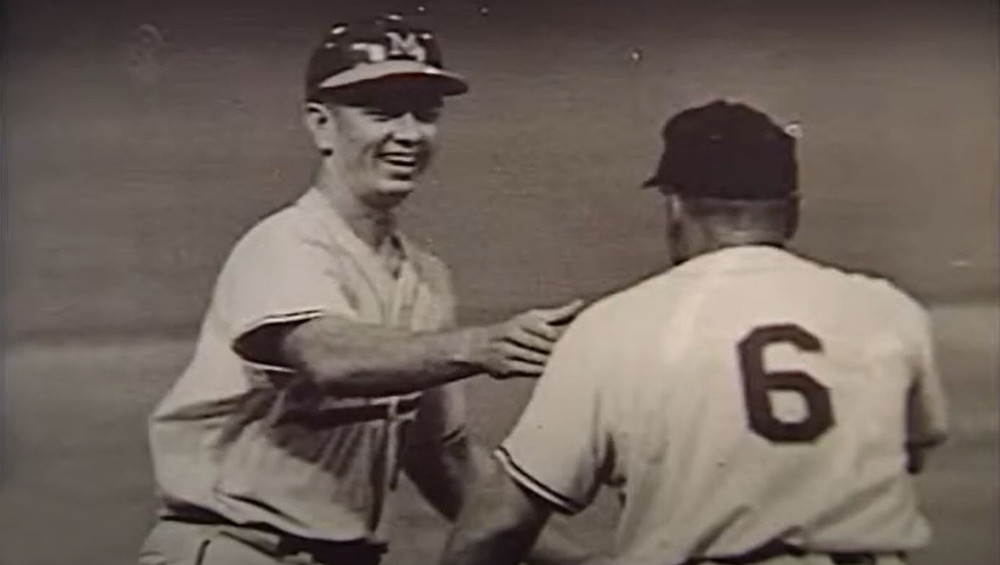

“I was going to try to change some things and I was going to go with the younger ballplayers, put in a different kind of philosophy and theory of playing the game,” Fraser said in Ernie’s UMSHoF induction video. “And Ernie was a senior and I kept Ernie because he was the kind of guy that I thought would be a good leader and he was. He was one of those guys that he led by his performance and everybody respected him and we had a better ball club because of him.”

Ernie rewarded his new coach by posting a dazzling .448 batting average that remains the third-best single-season mark in program history. He also set a then-Miami record with 42 hits and earned team MVP honors while playing second base and left field.

During her youth, Paige knew none of these incredible accolades. She simply knew he was a good ballplayer who spent some time playing in the minor leagues.

As she grew up, Paige began to learn more about all of her father accomplished at the collegiate level. That culminated with her father earning his UMSHoF call.

“We were all happy for him. I think, as I got older, in high school, I realized that some of the things he did for Miami baseball were pretty cool,” Paige said. “…[I was] more just proud that he gets recognition for a job well done than anything else.”

Paige actually missed her father’s induction banquet because it came during her freshman year of college at UCLA and she had a conflicting match.

It was her father who helped her even get in the position to play at UCLA, an elite program coming off a national runner-up finish when Paige joined the team.

“I had gone to UCLA as probably a 12- or -13- or -14-year-old and once I saw the stadium at UCLA, I said to my dad, ‘This is where I want to go. This is where I have to go.’ I remember, we were at the top of the UCLA stadium and it was like [a feeling of], ‘This is where I have to go to school,’” Paige recalled. “And he looked at me and he said, ‘Well, you’d better get a lot better.’ And you know what, that’s kind of how our house ran. I got my first recruiting letter from UCLA and who was the first face [I put] it in front of? My dad’s.”

That drive Ernie instilled in his daughter was a prime reason she was able to be so successful as an athlete in her own right. It also, sometimes, got her in a bit of trouble.

Paige remembers going to a prime junior tennis tournament with her mother. After jawing at the officials some, Carol told her if she did again, she would pull her from the tournament.

In an ensuing match, when Paige thought her opponent was cheating on calls and the official was not handling it properly, she said something to him. Then, as promised, her mother removed her from the field.

Upon returning home, Ernie asked what happened and she explained it to her father and then showed just where she learned her competitive fire from.

“My dad has this book and he has a lot of old articles of when he was in college or when he was in the minor leagues and when he played. And my dad was feisty. He was kind of like me; we have the same personality,” Paige shared. “I got the book out from the closet and I put it on the table because I was angry and I go, ‘Look.’ It was my dad at Mark Light Stadium and he had a guy at home plate and I guess they had a collision at home and they were in this huge fight. And I showed it to my dad and that was like my example to my dad of, ‘Come on, I’m just competing. How could she pull me out of a tournament?’

“My mom was always the calm, cool, collected one that literally would read a book while I played,” Paige continued. “When I went with my dad to tournaments, it was like the rules were a little bit different. Just because we definitely competed similarly.”

Ernie worked with both of his kids during their childhood on their respective sports, aiding Paige on the tennis court and Ernie Jr., on the baseball field.

His commitment to his children paid off, with Paige turning in an All-American career at UCLA and Ernie Jr., playing collegiately at Stetson before being selected by the New York Yankees in the 1992 MLB Draft.

As youngsters, the two would argue with one another each night on who would get to play with their father first when he got home from work. When tennis was the choice, Paige learned lessons that have served her to this day.

“He’d chip and drop-shot and lob and slice, and he would drive you crazy. And, at the time, when you’re 14, 15 years old, you kind of resent that,” Paige said. “I remember telling him, ‘Dad, come on! Feed the balls better. Feed the balls in my strike zone. These are horrible.’ And he would always tell me, ‘Paige, one day you’ll see why I do what I do.’ And I would look at him like, ‘Okay, whatever.’

“[Now, I tell my players] all the time, ‘Get comfortable being uncomfortable.’ I learned that from my dad at a very young age,” she added. “He didn’t know tennis technique, he didn’t know tennis strategy. He knew the basics—put the balls between the lines, have a great attitude, outcompete that kid on the other side of the net and work your tail off. And [if you do that], you’re going to go pretty freaking far. And he obviously provided great coaching for me. But I believe one of my attributes as a tennis player and even as a coach is just mental toughness. [That is] 100 percent from my dad.”

It was in 1998 that Paige began to use that mentality as a college coach. Just two years after graduating from UCLA, where her parents fully supported her going despite any wishes to have her nearby, she was coaching at her father’s alma mater.

After four years assisting Jay Berger—the latter two as associate head coach—Paige was promoted to the top spot in 2002 by then-Miami athletic director Paul Dee, himself a UMSHoF inductee.

Since then, she has guided the Hurricanes to at least the second round of the NCAA Team Championship each season, notching 13 trips to the Sweet 16, eight spots in the Elite Eight and one appearance in the national championship. Eight times her team has finished in the top 10, with five more top-15 finishes.

Fifteen of her players have claimed at least one ITA All-America honor, with two of them earning an NCAA Singles Championship crown.

“She got away from us as a player,” Remmert said, “but boy, we’ve sure made up for that in having her as our head coach for almost 20 years.”

There is no question the two-time ITA Southeast Region Coach of the Year has rewarded her employer during her illustrious tenure.

However, there is also no question serving as the head coach at The U is equally as rewarding to the coach herself.

“I know a lot of people probably do not believe this when I say this because in today day and age, you don’t hear it—I don’t feel like it’s a job,” Paige said. “I have been given the privilege for 23 years of doing something that is being involved in a sport at an institution that I have a special place for, in my home city, helping young people just try to get better.

“…To be able to be given the opportunity to work at a place like Miami where, obviously, I know so many great memories occurred for my dad, for myself as a coach, it’s special,” she continued. “It’s definitely special. It almost seems a little surreal; I don’t really ever talk about it much.”

Few people are more familiar with Miami’s rich athletic tradition than Remmert, who worked at The U from 1978-1987 before returning in 2012.

An encyclopedia of Hurricane history across all sports, Remmert counts the Yaroshuk story as one of his favorites.

“Here’s a father who was a great baseball player for the University. He has a daughter who comes back after her own tennis career out on the West Coast and she becomes just an extraordinary tennis coach for us,” Remmert shared. “I’ve always said that it’s the power of The U that brings great things out of people. Certainly, Ernie and Paige came to the table with greatness inside of them and I want to believe that the University and the ‘U family’ helped bring that out of them.”

The distinction as one half of the lone father/daughter duo in the prestigious UMSHoF is humbling to Paige, but it is not a major focus. She learned from her father, whose name will always reside next to hers in the Hall, that accolades are not what define who you are.

To Paige, luck is also a factor in their unique distinction, as she opines she may have garnered hall-of-fame recognition elsewhere if presented a chance at a different institution. By the same token, though, she acknowledges she might not have achieved that status elsewhere.

Fortunately for both parties, the coach’s opportunity did indeed come at the school she grew up cheering for and never stopped loving.

“Somebody made a decision to say, ‘Hey, you know what, Miami athletics is in this kid’s blood.’ And I truly believe that Paul Dee took that into account when he hired me because Paul Dee knew my background and there’s a lot to be said for that,” Paige said. “…You don’t think all those years of going to games and going to sporting events and seeing legend coaches before me helped me become the person I am today? Growing up in my house and seeing a great father, but also a great athlete—it all, I think, had to do with some of the success that I’ve had.”

Paige’s success, paired with that of her father, has formed one of the most prominent families in the history of Miami athletics.

The Yaroshuk name will live on forever in the annals of Hurricane lore—not once, but twice.