Nice Guys Don't Always Finish Last

Jan 3, 2003

By JIM LITKE

AP Sports Writer

TEMPE, Ariz. (AP) – How fitting.

At the end of a college football season where misbehaving was a centraltheme – coaches ripped referees and smacked fans, fans ripped down goal postsand rampaged through town – the national championship will belong to a coachwhose temperament doesn’t need icing down.

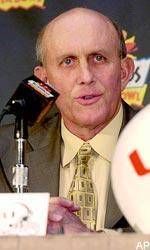

In that sense, it doesn’t matter who heads home with the Fiesta Bowl trophy:Miami’s Larry Coker or Ohio State’s Jim Tressel. A win by either proves thatnice guys don’t always finish last.

“The thing about Larry when you watch him on a day-to-day basis,”Hurricanes offensive coordinator Rob Chudzinski said, “is that he just enjoyswhat he is doing. You see head coaches who are stressed out. Whenever you seehim, he’s enjoying it.”

The same is true of Tressel. Watching him motor up and down the Ohio Statesideline in a crisp white shirt, red jacket and tie, he looks like a NormanRockwell painting come to life. While some of Tressel’s routines seem schmaltzyat times, none of his players doubts his sincerity.

Asked about his coach’s temper, receiver Michael Jenkins paused beforerecalling the first – and so far, only – time he saw Tressel get mad. It came afew days after the Buckeyes returned from a trip to Penn State and playerswearing headphones had a run-in with flight attendants.

“They called Coach into the cockpit, but he didn’t say a word about ituntil our next team meeting. Guys already knew he wasn’t crazy about themwearing headphones most of the time, so I guess we were expecting a lecture.But it wasn’t anything long,” Jenkins said. “What did he say? Put it this way- he hasn’t had to repeat himself a second time.”

Both coaches have no trouble being heard without shouting, in part becauseboth already own some impressive hardware. Coker won his first national titlein his first year as a college head coach. Tressel won four Division I-AAchampionships at Youngstown State.

It’s also not hard to figure out where either learned his chops. Both wereproducts of families led by fathers who taught them to work hard, to serveothers, and let that carry them as far as it might.

Coker grew up in Oklahoma the son of an oil field pump man who died at age89 in 2000, and a mother whose successful fight against cancer 40 years agotaught him lessons about toughness and survival that still drive him today. Heplayed defensive back at Northeastern State University, then made the segueinto coaching at Fairfax (Okla.) High, where he won two state titles.

In 1978, after moving to nearby Claremore High, he caught John Cooper’s eyeand joined the staff at Tulsa. Thus began the life of a coaching gypsy. He wasJimmy Johnson’s offensive coordinator at Oklahoma State, put in a stint withCooper at Ohio State, worked for Gary Gibbs at Oklahoma, and finally settled inwith Butch Davis at Miami.

He helped develop future NFL stars Barry Sanders, Thurman Thomas, EddieGeorge, Orlando Pace and Edgerrin James. Yet nobody but real college footballinsiders could have picked Coker out of a lineup. And if the kids at Miamihadn’t gone to bat for him when Davis left to join the Cleveland Browns, Cokerstill might be an assistant.

“We knew what would happen if Coach Coker stayed,” lineman SherekoHaji-Rasouli said. “As a group, we decided to push for it.”

In the way that sports takes strange twists, not only did Coker work at OhioState, but Tressel interviewed at Miami for the job that went to Davis, thenCoker.

“It’s interesting in life – usually things work out,” Tressel said. “Theymade the right decision in hiring Butch Davis and his staff. Things worked outfor all of us.”

In Tressel’s case, it wasn’t exactly coincidence. Born and raised in Ohio,his future was pretty much assured the moment his father let him tag along atwork. Lee Tressel was a legend in Ohio’s high school ranks by then, about torepeat the feat as a bow-tied presence on the sideline at Division III BaldwinWallace.

Dick Tressel, Jim’s older brother, got the earliest indoctrination andfollowed his father’s lead first. But there was little doubt Jim would take thefamily business the furthest.

Coker wondered whether he’d ever get this far. Some days, his job still hasa pinch-me quality about it.

“I tell a story at luncheons that I was the first new head coach to win anational championship in 53 years. Bennie Oosterbaan did it at Michigan. He gotfired the very next year. I remind myself of that as I go out and do thisthing. Maybe that’s why we did well this year. You know what? I’m not safeyet.”

Jim Litke is the national sports columnist for The Associated Press. Writeto him at jlitke(at)ap.org