Overcoming Adversity

CORAL GABLES, Fla. – Few University of Miami student-athletes in recent memory have dealt with as many crushing injuries as Yolimar Ogando.

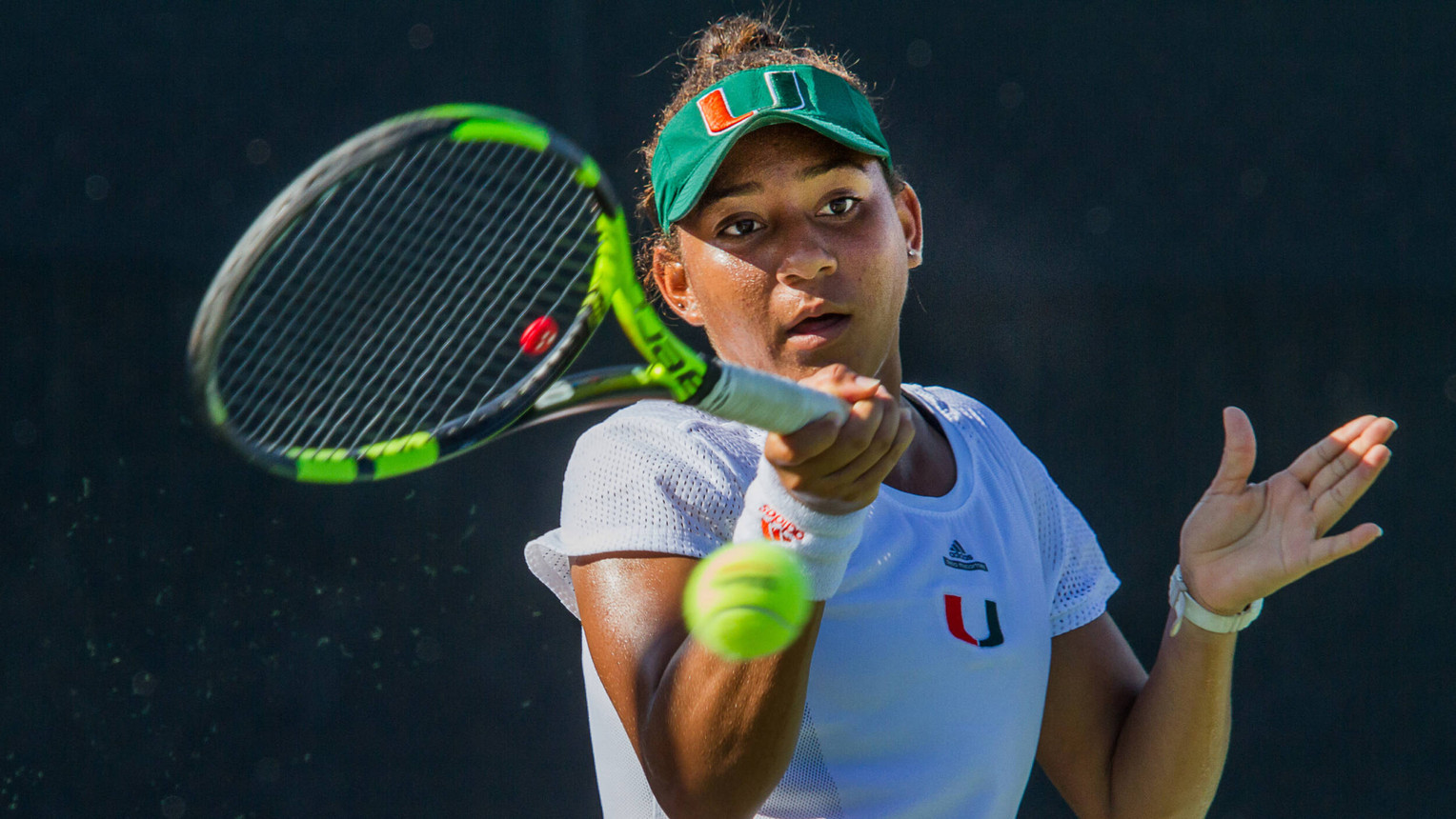

A member of the women’s tennis team, Ogando joined the Hurricanes in 2014 as a high-level recruit, placing second nationally in her class on TennisRecruiting.net’s rankings list. Her athleticism, explosiveness, ball-striking ability and maturity all excited Miami head coach Paige Yaroshuk-Tews.

However, the 5-foot-9 right-hander appeared in just six dual matches in her three years with the program, as a trio of injuries derailed and eventually ended her promising career.

“Maybe because of my junior level, they were expecting me to make a difference or be good,” Ogando shared. “I feel like I was never given the chance to fully immerse [myself into] the program and really be the best. I feel like I never really reached the best that I could be and so that’s something that will always stay with me.”

Although injuries sapped her of that chance, Ogando, now a week-and-a-half shy of her 24th birthday, can look back on her time as a Hurricane with fondness and even laughter, rather than sadness.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Ogando’s career got off to a rocky start, as she came to Coral Gables with a right wrist that was already bothering her.

The pain required her to take extended breaks between brief periods of practice. It also kept her out for the entirety of the fall campaign, while her three fellow scholarship classmates gained valuable early experience.

“It absolutely set her back,” Yaroshuk-Tews said. “You’re coming in, you’re transitioning to college and, on top of it, she hadn’t really competed prior to coming in for a few months because of the wrist.”

By the time the spring season came around in January, Ogando felt good enough to take the court alongside her teammates. She played in three matches in the Hurricanes’ season-opening invitational, including defeating Astra Sharma, who went on to clinch the national title for Vanderbilt that year and has since entered the WTA top-100 and played in four Grand Slam events.

However, Ogando did not see any further action until Feb. 20, 2015, when she made her dual match debut against FGCU. She played in five additional matches over the next month, but her season came to a halt after a March 20 outing against NC State.

“I think it got to a point where I couldn’t hold the racket,” Ogando recalled. “I was in a practice match with Monique [Albuquerque] and it was just so, so bad. That’s when we decided, ‘Okay let’s get it checked out one more time.’”

Ogando, who went 3-3 in her six dual match appearances, was diagnosed with a broken hamate bone that required surgery and shelved her for the remainder of the year.

Miami, without its much-ballyhooed recruit, still managed to post an 18-7 (12-2 ACC) record and reach the NCAA Sweet 16 for the 10th year in a row. Ogando, though, had to watch from the sideline.

“It was just frustrating not being able to compete, especially when I was still working out,” Ogando said. “I felt like I was still doing my part of it, it’s just that my body wasn’t ready. My body just wasn’t connecting with what I wanted to do.”

As disappointing as her lack of action was, Ogando managed to use it as a positive when she returned to Carolina, Puerto Rico, over the summer.

“I remember that I literally gave it my all when I went back home and I trained,” Ogando recalled. “I became the fittest that I ever was after that surgery.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Ogando came back to Miami in the fall of 2015 looking like the player everyone expected her to be before her wrist injury.

On a team featuring three players who eventually combined for six ITA All-America honors, Ogando was arguably the star of the fall. She won her first 14 singles matches, including six over top-90 foes, half of whom were in the top 50.

“It was very rewarding, I’m going to say, because I had worked really hard over the summer and, I think, just having the team back me up [meant a lot],” Ogando said. “I remember a few matches before I got injured, the team was on my court and they were so [invested in] cheering and so excited that I was able to play again and with the way I was playing again.”

The 14th and final victory of her winning streak was her most impressive one, a dominant 6-3, 6-2 triumph over No. 24 Brianna Morgan of Florida in the third round of USTA/ITA Southeast Regional Championships in Athens, Ga.

“There’s a time when you’re coaching these girls and you just know . . . they’ve turned the corner,” Yaroshuk-Tews said. “You know that you don’t have to be the light behind them every single day telling them to go. It’s like they show up one day and they’re on cruise control and that’s where Yoli was. Yoli found her tennis, she found her focus.”

Just one day after knocking off Morgan, on Oct. 25, 2015, Ogando’s 2015-16 season came to an end.

A game away from forcing a split against No. 38 Kourtney Keegan of Florida, Ogando charged towards a drop shot and stopped short of the bench on the side of the court.

“Now that I think about it, it wasn’t that close,” Ogando reflected. “It would have even been better if I would’ve kept running and I just fell over the bench, but I guess that when you’re in that timeframe, your mind just reacts and I just stopped.”

The sudden halt tore the ACL in Ogando’s right knee, although she did not know it at the time. In fact, she played two additional points, but felt her leg give out when she tried to serve.

Even still, Ogando did not think it was a serious injury and rather just a symptom of a tired body. She wanted to extended her perfect fall ledger and pursue an automatic berth in the prestigious Riviera/ITA Women’s All-American Championships.

“I could walk normally, I could do everything normally,” Ogando said. “So, it was like, ‘Should I retire? Should I not?’ But then I couldn’t serve.”

A few days later, Ogando got an MRI on her knee, which revealed the disheartening diagnosis. Ogando, though, had no idea what a grueling process the physical rehabilitation for an ACL tear was like.

After a quick, successful recovery from her wrist surgery, Ogando expected this to be a similar experience and that she would be back on the court in just a few months. It was not until a conversation with Yaroshuk-Tews that Ogando began to understand the magnitude of her new injury.

“I remember Paige telling me, ‘Yoli, this is not like your wrist. You need to stop comparing.’ I was like, ‘No. How bad could it be? I’ll get back to it,’” Ogando recalled. “I think everybody else was more concerned about it than me, just because I wasn’t as informed and just my previous surgery had been so smooth. Nobody could convince me that it was going to be a little bit more serious.”

After her surgery, Ogando began to truly see the difference and accepted that this injury was not like the one to her wrist. She initially got “very sick” and then had to deal with the beginnings of a strenuous recovery plan.

“For the first two weeks, it was just constant pain,” Ogando said. “I remember crying through rehab when they have to bend your knee.”

Ogando frequently spent time in the training room with a pair of Miami football players, Raphael Kirby and Darrion Owens, also recovering from knee injuries. The group developed a bond and helped one another along the way.

Furthermore, Ogando appreciated the constant care and understanding from the employees in the room, including Karl Rennalls, then the athletic trainer for the women’s tennis team.

“The big thing for us is that we understand. I’ve been doing this at UM for [seven] years now, I’m starting my eighth year,” Rennalls said. “We’ve seen people that have really struggled with their rehabs and people that have just flown through and you kind of have to pull them back. I think as time goes on and during the seasons, each sport will have a couple people that will have similar injuries. So, they’re able to push each other because they’re always in the training room getting better. And then, as far as the staff, I think we do a good job . . . [of trying to] make sure people, when they’re in there, they know that we care and we want them to get better.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

As Ogando entered the beginning phases of her rehab, the spring campaign started for the Hurricanes, who knew they would be playing the whole season without their sophomore standout.

Miami still turned in a dazzling year, posting a 21-6 (12-2 ACC) mark that included 15 straight wins, yet another NCAA Sweet 16 berth and a top-10 ITA finish.

Ogando, who earned a No. 21 national ranking from her stellar fall performance and capped the spring at No. 50 despite not competing, did still help her teammates through coaching. That led to both exasperation about her inability to play and a mindset of acceptance.

“From the outside, when you’re coaching, you also realize a lot of things. You’re not as tired and you see the court more, with a new perspective,” Ogando said. “So, there were times I was like, ‘I want to play, I want to play! I know how to beat this girl!’ It was just frustrating sometimes to see it. I definitely thought that we had a good team, but I don’t know, anything can happen. So, I was like, ‘Even if I was on the team playing and we were better or not, it’s just not meant to be.’ I had so much confidence in all of them that, even if I was playing or not, it was such a good team.”

As her teammates racked up win after win, Ogando rehabbed diligently to join them back on the court as soon as she could, whenever that may be.

Rennalls, who worked hands-on with Ogando on a consistent basis throughout the spring, even had to ask her to tone down her efforts at times.

“I remember as soon as it was allowable, she was like, ‘Alright, can we go out and I’ll just sit on a chair and just start hitting the ball?’ She just wanted to be able to get the racket in her hand and be able to do as much tennis as she could,” Rennalls said. “So, I remember there would be times where we’d be like, ‘Yoli, we have to pull back just a little bit.’ Because she wanted to do a little bit too much or get a little too aggressive with what she was doing. I think . . . she was always trying to do the most she could to be as close with tennis as possible.”

Ogando came to understand that she had to pace herself and eventually got cleared to resume competition.

“I was 100 percent back on,” she said. “My leg was as strong as before, as flexible.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

When the fall of 2016 came around, Ogando was indeed ready to go. Encouraged by the words of her coaches and athletic trainers, she began to trust her knee once again.

Additionally, Ogando took the court with a new mentality.

“It just felt so good. I remember just being grateful for being healthy again,” Ogando said of returning to action. “I remember I was practicing and I was like, ‘You know what, it doesn’t even matter if I win or lose or scores, whatever. I want to play, I want to be the best and just stay as healthy as I [possibly can].’

That health lasted through a solid 9-4 fall campaign, but it did not extend much longer.

Ogando posted a straight-set, top-75 win on Jan. 20, 2017, to open her spring campaign, but that proved to be the final completed match of her college career.

In the first set of her contest the next day, still in the season-opening invitational, Ogando re-injured her right knee. She hit a backhand and heard a pop, but briefly tried to continue. She played two more points, but felt her knee give out during serves, just as it had 15 months earlier.

Ogando knew what that meant.

“I remember telling Paige, ‘It happened again.”

This time it was actually worse. Along with re-tearing the ACL in her right knee, Ogando also tore her meniscus.

“I wanted to smash everything, basically. I remember I was so frustrated, I was crying,” Ogando said. “Yes, I’m laughing about it now, but it was definitely so frustrating and sad. I think it was mostly sad because I had worked so hard.”

Dreading the thought of a second knee surgery, Ogando also had to decide if she wanted to continue her tennis career after going under the knife. Eventually, she understandably determined the rewards did not outweigh the risks.

“Mentally, I just felt like if I ever got back, I was going to be constantly thinking about it,” Ogando recalled. “. . . The doctors also said, ‘Look, you’re strong enough, that’s why it didn’t hurt when you tore it. We can’t give you [a guarantee].’ It was like a 50-50 chance that it was going to happen to again. I was like, ‘I’m not going to take a risk.’

“I want to be able to run and walk and ride bikes if I have kids, just stay healthy,” Ogando continued. “So, I was like, ‘If I have another surgery, what’s the chance that I’m going to be able to have a normal life, which is what I want?’ So, I’d rather stop playing and have a normal life than play again and risk it getting worse.”

While Rennalls no longer served as the women’s tennis athletic trainer in 2017, moving on to a different sport, and did not directly advise Ogando on her decision, he fully understands her choice at the time.

In fact, it is a general concept he preaches to the individuals he works with when they suffer serious injuries.

“How I always talk to my athletes is, I want them to be able to do their sport with their kids in the future,” he said.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Once Ogando made the call to stop playing tennis, it came time to accept a future in which the sport was no longer a central part of her life.

“It was very devastating for me. There was a period of a few months that I was not concentrated on school. I didn’t want to talk to people,” Ogando said. “I was distancing myself from, maybe, the people who care most about me and love me because I was just so frustrated. I was dedicated to this sport since I was seven years old and now finally I have to stop without even getting a fair chance.”

Ogando recalled one particularly tough day in the spring of 2017 during which she spent an entire class period crying.

“I want to be able to run and walk and ride bikes if I have kids, just stay healthy. So, I was like, ‘If I have another surgery, what’s the chance that I’m going to be able to have a normal life, which is what I want?’ So, I’d rather stop playing and have a normal life than play again and risk it getting worse.”

A teammate in her class, Ana Madcur, texted Yaroshuk-Tews to share what she saw. The coach, who previously never had a player tear an ACL even once, came to campus late at night to check on Ogando.

“Tennis isn’t more important than your health and I just completely supported [her choice],” Yaroshuk-Tews said. “Emotionally, just going through that, I think she just needed to know that people supported her.”

While she appreciated the care from her coach, whom she said never second-guessed the decision, it was still difficult for Ogando to envision what her new life would be like.

“It was very sad those first few months. I was like, ‘What’s my plan b? All my life I thought I was going be a pro. What am I going to do now?’” Ogando shared. “Yes, I was studying accounting, but it never [was my initial top option]. I was always like, ‘No, play for a few years professionally and then I’ll go back.’”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Despite the initial uncertainties, Ogando figured out her post-tennis journey and did so in grand fashion.

She graduated from Miami in 2018 and added a master’s degree in 2020. Just a few weeks ago, she started a job at Lennar Corporation as an accountant, putting her major to good use.

“I feel like I can handle so many things that come my way, especially situations at work or situations in my personal life. It’s just like, ‘Okay, if I can [go through those injuries], then I can do practically anything that I set my mind to,’” Ogando said. “Having to figure out my professional life and the business world, it’s just very rewarding . . . and at the end of the day, if it’s your dream or your second dream or whatever it is, then you always have a chance to prove yourself and be the best you can be at whatever you decide, even if that changes over time.”

While tennis is no longer an integral component of her daily routine, Ogando still gets on the court every so often for stationary hitting.

Her path after college may not have been what she initially dreamed it to be, but for Ogando, what she has now is more than enough.

“It’s just incredible when you think about it as a whole, how your life changes so [suddenly], but everything happens for a reason,” Ogando said. “I can’t complain [about] where I am right now and all the beautiful things that I have. I owe a lot of that to tennis, so tennis will always be a part of me.”