"To be back in the weight room, on the track and on the field doing hard things with your teammates, that’s what college football is about.”

Quarterback D'Eriq King

'Many Hands Make the Load Lighter'

Chapter Selection

CORAL GABLES, Fla. – It was a moment that, at one point, she wasn’t sure was possible.

And so, while she watched from afar last December as the Miami Hurricanes took the field at Camping World Stadium for the final game of the season, Dr. Erin Kobetz let the emotions wash over her.

She fought back tears. She recalled the highs and lows of the past seven months.

And she felt pride—overwhelming, undeniable, unabashed pride.

“I felt—and still feel—so unbelievably proud. There was a bit that felt somewhat surreal, like it was a dream, but I’d be lying to say I didn’t choke up a bit watching them run onto the field because I know how much work went into getting them there,” said Kobetz, the vice provost for research and a professor in medicine, public health sciences and obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. “In Haitian Creole, there’s a saying: ‘Many hands make the load lighter’ and watching those boys run onto the field was a really tangible example of how when many hands work together, we have the potential of accomplishing great things.”

Months before that emotional moment, Kobetz’s interactions with the Hurricanes had been pretty limited.

Of course, she cheered for her hometown team—especially after joining the University community in 2004 after completing her PH.D. at the University of North Carolina.

But early in the summer—as the Hurricanes, the South Florida community and the world at large—tried to come to grips with the worsening COVID-19 pandemic, Kobetz—who had been leading the University’s coronavirus testing, tracking, and tracing efforts—became one of the many hands working to develop a plan to keep Miami’s student-athletes healthy.

She joined a host of medical experts and administrators across Miami’s campuses and within the Hecht Athletic Center that were determined to make sure the Hurricanes had all the resources they’d need to compete in a season that, at that point, no one was certain would happen.

Still, there was optimism that football—and college sports, in general—would return sooner rather than later. So, with encouragement from University President Julio Frenk—who, as the former Minister of Health in Mexico had navigated previous pandemics—the Hurricanes began the work of preparing to play football again in June.

Their team meeting rooms, athletic training room, weight room and locker room were retooled to accommodate recommended social distancing guidelines. Personal protective equipment was acquired to protect both players and staff. Meeting and meal guidelines were changed to limit contact and any potential exposure. A testing center was set up in the Hecht Athletic Center. Contact tracing protocols were established and slowly but surely, the Hurricanes returned to campus.

It was, for many of them and their coaches, their first bit of normalcy since March, when spring practice was abruptly cut short by the pandemic and Miami pivoted to remote learning.

“I felt like when quarantine happened, I was just starting to get to know those guys, so when we got back, it was awesome,” said quarterback D’Eriq King. “Even though it was small groups of no more than like 12 or 16 people and once you were done working out, you had to leave the building, it felt great. Just to be back in the weight room, on the track and on the field doing hard things with your teammates, that’s what college football is about.”

An Uncertain Summer

While getting in some much-needed summer conditioning work was the first step in the process of getting the Hurricanes back on the football field, uncertainty still reigned.

As June turned to July, the questions about whether football could be played safely in a pandemic only got louder and louder and in South Florida, the number of COVID cases rose seemingly on a day-to-day basis.

Though he remained hopeful, Blake James – Miami’s director of Athletics – wondered if the season would happen, even as university presidents and medical advisors across the Atlantic Coast Conference discussed their options.

Kobetz even considered herself a “sideline skeptic” and during a video conference with football players and their parents, she noted more than a few were worried, an understandable sentiment given how much was still unknown about the coronavirus at that point.

Still, she was willing to continue trying to find a way to keep players as safe as possible while letting them compete in the sport so many of them had loved their entire lives.

Taking football away, she knew, could take an unexpected toll on Miami’s players.

“You don’t come to the University of Miami to play football if you don’t think there’s some possibility of this being what you’re able to pursue professionally,” Kobetz said. “A lot of these kids are coming here because it’s their chance to be on a national stage and for their talent to be spotlighted, which could then springboard them to a career in the NFL. I can imagine how overwhelming that would be for a senior or junior who is potentially going to miss out on a season they might see as personally defining for them to make that leap to the pros.”

Added Dr. Eric Goldstein, Miami’s sports psychologist, “I think for so many of these kids, who they are is based on their sport and their accomplishments. You take that away and there’s a loss of identity. There’s a sense of sort of the ground shifting underneath them. That’s where anxiety comes in. That’s where uncertainty creates more anxiety. … I don’t know what would have happened if the season was canceled for some of these kids’ mental health. That’s why I think it was really important to [try], as long as it could be done safely. Safety was going to override everything.”

Hurricanes head coach Manny Diaz was determined to do his part to keep players safe, too.

Along with accepting the guidance given to him by Frenk, Kobetz and the rest of Miami’s medical experts, Diaz spent time poring over game film studying just how much close contact occurred on a given play. How much time did a defensive back and receiver really spend together on a downfield pass? How long were offensive linemen truly blocking their counterparts on the defensive side of the ball?

“The sport of football is a game that involves a lot of close contact and to play football, you have to practice football,” Diaz said in August ahead of Miami’s first practices. “We understand our guys will be together. We’ve put clocks on that. We understand exactly how much time that is, and everyone would probably be surprised at how little time—during a two-hour practice—players are in close contact with one of their teammates.

“The other things we can control, whether it’s individual drills, drills in the past we won’t be doing this year. The way we stand when we’re not actively participating, all of that is going to be different. And that’s the whole point—we have to control what we can control and that’s the amount of close contact that our players have.”

Diaz shared the data he gleaned from that film study with Kobetz and over time, that film from Miami’s practices and games became an invaluable tool not just in helping the Hurricanes prepare to face their next opponent, but in the program’s contact tracing efforts. And Kobetz noticed that the more she studied the film, no discernible pattern emerged of COVID transmission happening on the field.

“I think Coach Diaz was really sort of at the forefront of coaches in thinking about how the film he normally reviews to figure out how the team can play better was a very critical source of data in the pandemic,” Kobetz said. “I give him a ton of props.”

But even with all the safety measures Miami—and schools across the country—implemented, there was still plenty of skepticism.

Revamped non-conference schedules that limited travel and built-in time for games to be rescheduled as needed were released, but concerns remained, particularly when it came to the matter of COVID’s potential long-term effects.

By the first weekend in August—just as many teams across the country prepared for their first practices of training camp—there were whispers Power 5 conferences were on the verge of canceling their seasons. Those whispers only intensified when on Aug. 8, the Mid-American Conference postponed all fall sports, a decision that made it the first FBS conference to cancel its football season.

Meanwhile, Connecticut—an independent FBS program—had already announced its decision to cancel football, too.

The drumbeat for cancellation across the country got louder and louder and the biggest question became which Power 5 conference would be the first to pull the plug.

The ACC, though, pressed on.

“I don’t think there was ever a moment that I got to the point of saying ‘Okay, this isn’t going to happen.’ There were points where I questioned if it would happen, but I never got to the point that it wouldn’t,” James said. “There were a lot of challenges within the community. Then, when the Big Ten and the Pac-12 announced that they were not going to play football, you weren’t sure where the SEC and the Big 12 were. But I think the presidents in our league, [former ACC] Commissioner [John] Swofford, the athletic directors, our medical advisory group really had great alignment through it all. … There was a commitment of the leadership of the conference that if we could figure out a way to do this the right way from a health and safety perspective, to move forward. That is why the medical advisory group was so critical. … I never got to the point of thinking it wouldn’t happen. Maybe part of me is an optimist and part of me really wanted to see it happen.”

There were, obviously, others who felt the same way. That first weekend in August, they tried to make sure their voices were heard, too.

The Players Speak Out

After the MAC’s announcement and as Power 5 football hung in the balance, a growing number of college football players across the country took to social media to share why they wanted to see a season happen.

Several high-profile players—including Miami’s own Greg Rousseau—chose to opt out of the season, some deciding to focus on their professional futures, others taking advantage of the NCAA’s decision to grant all student-athletes an additional year of eligibility.

But on Twitter and Instagram, others began detailing why they wanted to see a season happen. They shared images of themselves playing in games or preparing for the season. They tagged the posts “We Want to Play,” while their coaches shared reasons why they wanted to coach.

The “We Want to Play” movement—led by the likes of Clemson’s Trevor Lawrence, Ohio State’s Justin Fields and King, among others—took off, with players coordinating the timing of their posts and many of the players’ parents voicing their support for a season, too.

The effort came weeks after many of those same players spoke out on a number of social justice issues after the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor helped spark the Black Lives Matter Movement.

Both movements seemed like watershed moments for student-athletes across the nation.

“It was difficult to navigate the uncertainty, but again, that’s where I have to give credit to the players, not just ours but all around college football,” Diaz said. “I think it was a little bit of one of the themes of 2020 – the players were really finding their voices, whether it was on social justice issues or in the pandemic. Everyone was speaking for them. ‘How dare we? How can we? How stupid would we be to play a season?’ and then that one weekend, some of the higher-profile players in college football took to social media and said, ‘We want to play.’ If not for their voice, I don’t know that it would have happened. To that point, a lot of people were speaking for them.”

Said King, “I love football so much, so I always, always wanted to play. I really thought we should do it. As long as the schools could protect us as best as possible, I thought it was a good idea to play and give us some normalcy. It was a lot last year. It wasn’t just COVID. It was Black Lives Matter, too. There was a lot going on and I feel like a lot of us just felt it was safe to play. It’s what we know how to do. It’s what we love to do. And playing football is kind of like an escape for us, you know?”

Merely saying they wanted to play wasn’t enough, though.

If a season were to happen, student-athletes would have to do their part by taking on the responsibility of protecting themselves and their teammates. Sacrifices and adjustments would have to be made.

Along with adhering to testing and safety protocols on campus, Diaz stressed the need for players to be responsible when they were away from the football facility, even as a growing number of businesses and restaurants across South Florida opened their doors again and more students returned to Miami’s campus.

Mask-wearing became even more essential. Social circles were tightened. Off-day visits to see family or friends in South Florida were limited.

“We couldn’t have meals together as a team. There were no bonding events. A lot of the things that are fun about this game, that build camaraderie in this game, you couldn’t have this year,” Diaz said. “And then obviously, the players when they weren’t around us, the decisions they had to make in terms of what they did socially, the sacrifices they had to make, staying in their rooms, not being out and about, it was a 24-7 endeavor. It wasn’t just their four hours here in the building. … It was something they had to be cognizant of at all times because they didn’t want to be the guy that brought it in the building.”

Said James, “They really bought into the direction that was given to them and they went out and executed the plan that the UHealth team had put in place that allowed us to continue on. That ultimately got us to game day and then having a season. The approach our students and coaches took to that probably was one of the keys to our success and definitely one of the keys to us being able to move forward.”

Miami’s players weren’t the only ones asked to be cautious in order to help make the season possible. Coaches and staff adhered to the safety protocols, too. Student managers made the same social sacrifices players made and, Diaz pointed out, did so knowing they wouldn’t experience the glory of taking the field on Saturdays.

The Hurricanes did their best to take the suggestions from Miami’s coaches and medical experts to heart. Some woke up earlier than they were used to for early-morning socially distanced workouts. Visits with mom and dad were replaced with video chats or drive-by visits. Meals with teammates were replaced with packed to-go boxes that were eaten at home, alone or with their roommates.

The players’ voices were heard, their efforts to stay safe noted. The ACC, SEC and Big 12 eventually opted to proceed with their seasons and bit by bit, the preparations for Miami’s season-opener against UAB continued.

The Season Arrives

Before living with COVID, social distancing and mask-wearing became a part of life in South Florida, for Miami, there was plenty of excitement ahead of the 2020 season.

New offensive coordinator Rhett Lashlee, hired in January, brought with him a high-powered, high-octane offense that promised a much-needed spark. King, an established quarterback with a successful track record at Houston, arrived in Coral Gables, as did two other big-name transfers, defensive end Quincy Roche and kicker Jose Borregales.

Several Hurricanes playmakers including safety Bubba Bolden, defensive end Jaelan Phillips and tight end Brevin Jordan were coming off injuries and expected to give Miami a boost when the season eventually began.

Though the 2019 season had ended with a tough loss to Louisiana Tech in the Independence Bowl, the new-look Hurricanes were generating plenty of buzz when they took the field in March for their first spring workouts.

Six months later, they’d arrive at Hard Rock Stadium for their season opener with little fanfare.

COVID had changed everything—including, of course, the game day experience. As Miami’s team buses rolled through the near-empty parking lots around the stadium, Diaz and his players were reminded again of how different this season would be.

They weren’t the only ones taken aback by the socially distanced crowd of just 8,153 fans spread out amongst the stadium’s 65,000 seats.

No students were there that day. No cheerleaders. No Band of the Hour. There wasn’t even any of the piped-in faux crowd noise that had emerged in other sports settings around the country.

That game, that kickoff, was just another surreal moment in a season that was quickly shaping up to be something completely different than anything any of the Hurricanes had ever experienced.

Unusual as it was, though, the game brought something few in South Florida had felt in months—even if it was for just a brief four-hour window.

“When that ball kicked off against UAB, it was like, ‘Wow. Not only are we going to play football,’ but I remember thinking for a moment that something felt normal and nothing had felt normal before that since March 17th,” said deputy athletic director and football administrator Jenn Strawley.

Miami won that night, its 31-14 victory over the Blazers becoming the first of eight on-field wins to come in 2020. But that result was just one part of what had been a successful week.

In the days leading up to their opener and ahead of every game, the Hurricanes had to navigate a series of COVID tests. Any positives triggered immediate quarantining and contact tracing that would keep players from practices and games.

Getting to game day was a victory in and of itself and an hour before every kickoff, a list of any unavailable players was made public. Game plans were adjusted throughout the week and making that task even tougher was the fact that players who didn’t feel their best were required to stay home until they felt better, even if they hadn’t tested positive for COVID and were dealing with something as simple as seasonal allergies.

An abundance of caution was always taken, and it was an approach players and coaches understood. But that didn’t mean it wasn’t challenging.

“Every day when you came into the building, there was going to be some bit of unexpected news. Every day. It wasn’t always bad, but generally speaking, there was always something you thought you might have had [a handle on] and then the next day, it was different,” Diaz said. “What people don’t even realize is, it wasn’t just the actual cases of COVID, or the contact tracing. If a player had a cough that wouldn’t stop, they couldn’t come in the building. They woke up with a headache, they couldn’t come in the building. You would lose player practice days not just because of actually testing positive or being in contact tracing.

“Every week, there would be 3-4 guys that would miss, just with symptoms that in any other normal year, you wouldn’t have thought of twice. Every day, you were going to come into the building and before practice, you were going to find out somebody we expected to have, we weren’t going to have, and you just managed. I think the amazing thing for the players and the staff is that everybody just rolled on. Whatever it was, whatever we had, we just managed, and we knew that 2020 would be about whoever could adapt to the situation at hand because nothing would be normal. And again, I think the players did a really nice job with that.”

“Staring at the Brink”

Through ups and downs on and off the field, the Hurricanes navigated the first seven games of the season. They shone on a national stage against Louisville in their ACC opener. They were a dominant force in a historic win over rival Florida State and fought through a loss to top-ranked Clemson. They won three straight after that and showed their mettle in hard-fought victories over then-defending Coastal Division champion Virginia and North Carolina State.

As Miami began preparing for its Nov. 14 game at Virginia Tech, though, trouble loomed. And when the Hurricanes gathered for a practice that week, Diaz couldn’t help but wonder if the trip to Blacksburg would even happen.

“It might have been that Wednesday of the Virginia Tech week. We had dropped a bunch of guys throughout the week. We lined up for our pre-practice stretching period—and we’d already made that different where everybody was spread out across the field, 10 yards apart. When we did that, it would take up the majority of the indoor facility,” Diaz recalled. “Where we would normally have over 100 guys lined up, that day, I don’t know if we had 50 or 60. You could see the difference in numbers, where lines were missing. That was really a strange moment in terms of how odd 2020 was.”

By Friday, the Hurricanes were, as Diaz described it, “staring at the brink.”

The coach drove to campus still unsure if the Hurricanes would fly to Virginia. The team’s final round of on-campus testing wasn’t encouraging, but players were adamant—they felt they could be competitive, even with their limited numbers.

Diaz consulted with his coaches, who shared the players’ belief the game could be played—as long as the Hurricanes could avoid any in-game injuries.

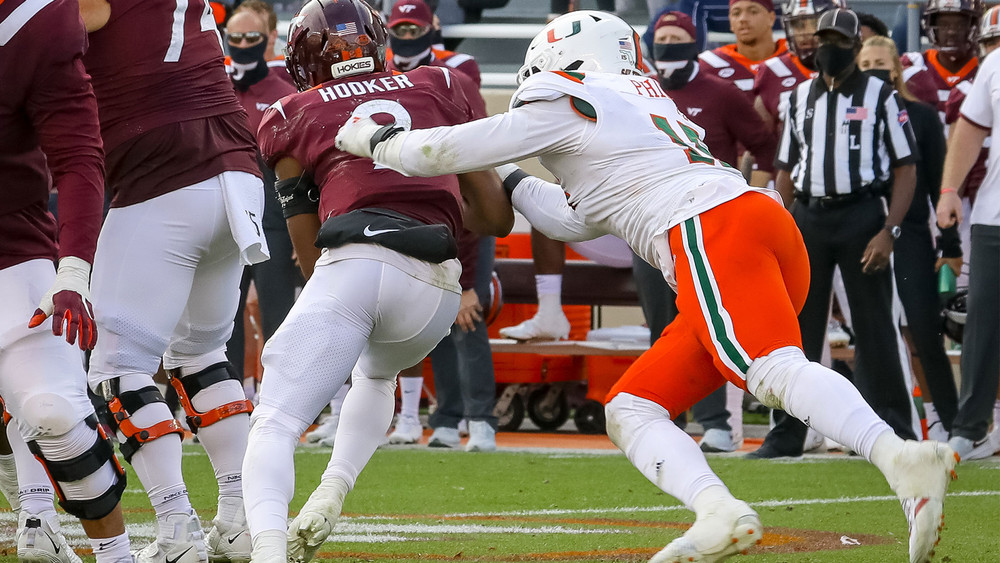

Though they’d eventually be without 13 players, the decision was made that the Hurricanes could play safely, and an energized group headed to Blacksburg, still knowing a final round of pre-game testing would ultimately determine whether the game would proceed.

A day later, the Hurricanes had won their fourth in a row, with King leading another second-half comeback and the defense holding strong during Tech’s final possessions to secure the 25-24 victory.

“I think that was one of our more gratifying wins of the season,” Diaz said. “We went through a lot of adversity that week to be able to field a football team.”

It would be weeks before the Hurricanes played another game.

Covid Hits Home

In the days immediately after the Hurricanes returned from Blacksburg, it became increasingly clear to Diaz, James, Strawley, Kobetz and all of Miami’s medical experts that COVID had found its way into the football program, despite everyone’s best efforts to keep the virus at bay.

It didn’t exactly surprise Kobetz, who had been tracking COVID spikes both in South Florida as a whole and on Miami’s campus itself during the same time period, she said. But it was stressful—and at times, scary.

As more players and staff began testing positive, quarantines began. Devices that helped players monitor their temperatures and blood oxygenation were handed out. Telehealth appointments were set up so players could speak with doctors remotely. Goldstein checked in daily with players in isolation and as some players began recovering, their cardiac health was tested before any could even consider getting back to workouts.

The final three games of the season were rescheduled, with matchups against Georgia Tech, Wake Forest and North Carolina all pushed back. The schedule would be adjusted further when some of Miami’s opponents dealt with COVID issues of their own.

As the ACC reshuffled Miami’s schedule, the Hurricanes dealt with their outbreak. Some players and staffers were completely asymptomatic or coped with minor nuisances like manageable headaches.

King and Diaz both announced they’d tested positive, with the quarterback saying he hoped to shed light on how difficult it could be to avoid COVID, even when trying to be as cautious as possible.

Others within the program, though, faced tougher challenges.

Vinny Scavo, Miami’s associate athletic director for athletic training and the team’s head trainer, shared on social media that he was hospitalized after his diagnosis.

It was a sobering moment not only for the beloved trainer and his family, but for all the Hurricanes.

“When I got it, at first, I never lost taste or smell. A lot of people did that. It was like I had the flu for a couple days. And then that Tuesday before Thanksgiving … I couldn’t breathe right and I couldn’t hold a conversation without coughing continuously,” Scavo said. “Friday, I went to [University of Miami Hospital]. I waved goodbye to my wife and daughter thinking I was going to get a chest X-ray and I didn’t get out until late Tuesday night. It was the best of the best at that hospital. Those people don’t get enough credit. They were the absolute best of the best.”

That stretch—between the Virginia Tech game on Nov. 14 and Thanksgiving—proved some of the most difficult days Miami faced.

“It was real tough. Obviously, it impacted different individuals at a different level. When you go from having people in the hospital to an individual who said ‘Honestly, had you not tested me, I would have never known I had it,’ it was such a spectrum in terms of how it impacted individuals,” James said. “For those that it hit hard, obviously, we were concerned. You want to do what you can to help and it’s hard to know what that is because you can’t go see people and be emotionally supportive. You can text and those types of things, but it’s hard anytime you see someone go through something like this.”

Said Diaz, “I can see why this can be such a misrepresented disease. If you just know stories anecdotally, you can find somebody who can tell you it wasn’t a big deal, and you can find someone that can tell you it was certainly a big deal. On the team, we got to see the spectrum of it all. That was tough, and you wanted your team to be well. The second element of it all is the isolation and this is where it goes back to the mental health aspect of it all. The day I was told ‘You have it,’ I went home, picked out a room and basically just said ‘I’m going to be in this room for 10 days.’ That was weird. It was Thanksgiving and my family is having Thanksgiving inside and I’m sitting on our back patio, looking through a window. … So many of our players had multiple contact-tracing, 14-day isolation periods and that was hard. … Talking to a lot of the players, that was, to them, as difficult as the disease itself.”

Getting Back to Work

As the Hurricanes navigated their outbreak, King wondered if Miami’s rescheduled games would ultimately be played.

Eventually, some of them were.

Players recovered. Coaches and staff did, too. Cardiac testing of impacted players continued and a game at Duke was added as the ACC adjusted schedules again as COVID impacted teams across the conference.

On the night of Dec. 5, Miami returned to action—and with 15 players still unavailable, earned one of its biggest victories of the year.

Playing in an empty Wallace-Wade Stadium in Durham, the Hurricanes dominated in a 48-0 win over the Blue Devils. The game marked Miami’s first ACC shutout since the Hurricanes joined the conference in 2004 and its first shutout of a Power 5 opponent since beating Syracuse in 2001.

Even in a quiet stadium, there was plenty of life on Miami’s sideline.

“It’s hard for people to actually understand how excited they were to get back on the football field and you saw it, you saw it in that game and how they played,” Strawley said. “The energy of it all was overwhelming.”

Said King after the win, “Everybody was excited to come out there and play. Just having three weeks off, sometimes you could take playing football for granted. I know getting back in the building, it was a different kind of energy. I think our coaches did a great job all week of trying to get us prepared, trying to get ready for the game and we came out here today and I think we cut it loose.”

That energy, though, didn’t last.

After that emotional win, the Hurricanes struggled mightily in a loss to North Carolina a week later. The game was forgettable on a number of levels and with the team not all that removed from the emotional toll of the COVID outbreak, some wondered if the stress of the past month had finally caught up to the Hurricanes—particularly as some teams across the country opted to cut their seasons short and bypass postseason bowl games.

Miami, though, chose to play in its bowl game—a Cheez-It Bowl showdown in Orlando against Oklahoma State. That night proved an emotional one on multiple levels as the Hurricanes fell behind, lost King to a knee injury and rallied before ultimately, coming up short in a 37-34 loss.

Despite the result, Kobetz wasn’t the only one to feel pride that night.

“I still go back now and when I watch the film of that game, I just look at our sideline in the background, the way the players were energized, into that game, positive, optimistic, fighting for each other and giving everything they had. It was remarkable,” Diaz said. “I don’t think anyone on that sideline thought we were going to lose that game until the very last second when we ran out of time. They fought so hard for each other and losing sucks. We feel like we shouldn’t have lost that game, but that experience, it’s something to take away from this team, how hard those guys played for each other that night.”

Lessons Learned

There is a lot more, of course, Miami will take from that night and the season that was.

While no one is certain what the world—and sports—will look like this fall, the Hurricanes feel they now have a playbook of sorts for dealing with any kind of potential challenge, including, of course COVID.

There are safety protocols in place that will remain in effect as long as necessary. Much more is known about the virus today than was last August. And a growing number of Americans are receiving vaccines that public health experts across the country believe will only help drive down infection rates.

On top of all of that, the Hurricanes truly learned the value of teamwork—and it extended far beyond the walls of the Hecht Center or the field at Hard Rock Stadium.

“Many hands” helped the season happen. That is something no one at Miami takes for granted.

“You certainly feel like you can adjust to anything right? There’s a lot of things we say, ‘It has to be done this way’ and we found out they don’t have to be that way because none of us had it that way this year,” Diaz said. “Even though it wasn’t ‘normal,’ we still functioned as a football team. … Nothing stayed the same. But it showed we can adapt. It means you can find out what’s really important. And I think that’s the takeaway for everybody.”

Said Kobetz, “We have the benefits now of lessons learned. We do have that playbook. We know what really worked and can use that as a foundation to build future success. Relationships have been established as a function of COVID and we’ve built a stronger connection and community at The U. … We know we can count on each other to do hard things.”