Hurricane Heavyweight

CORAL GABLES, Fla. – In Raphael Akpejiori’s fourth sparring session, he broke his ribs.

That was when he knew he wanted to be a boxer.

“I was out for like five weeks and my head was just hurting. Everything was just hurting. That’s when I started questioning myself, like, ‘Oh my God. Do I really want to do this?’ And that’s when I finally decided, ‘Yeah, this is fun. I like it,’” Akpejiori recalled. “And I started getting better within those five weeks that I couldn’t really do anything. I started watching the sport. I started watching the legends—Floyd Mayweather, Lennox Lewis, Errol Spence. Gennady Golovkin was my guy at that time.”

A forward on the University of Miami men’s basketball team from 2010-14 and a tight end on the Hurricane football team in 2014, Akpejiori got into boxing not long after departing college.

He graduated from a five-year program in 2015 with a master’s degree in mechanical engineering and shortly thereafter began working at his alma mater. He took on a role in the University’s facilities management department, serving as an energy engineer with a focus on reducing the school’s costs in electricity, water and natural gas.

Despite working for five years to put himself in a position to have a job of that caliber, something was missing for Akpejiori.

“Competition gives me life. It’s all I’ve known,” Akpejiori said. “…When I got my job and I was working, I just was not myself. Just going home, working, sitting down, eating, going to a bar … it was just not my thing. I just had to do something that was competitive and that’s how boxing started for me.”

The sentiment Akpejiori expressed is one echoed by Jim Larrañaga, his coach at Miami during his final three seasons on the hardwood.

Akpejiori left a lasting mark on the two-time ACC Coach of the Year with both his physicality and his mentality.

“Raph is probably as physically tough as any player I’ve ever coached. He loved contact. He was an imposing specimen; 6’8, 240 to 250 pounds of sheer muscle,” Larrañaga shared. “One of the interesting things, I think, about Raph is he’s so competitive. In the classroom, he was competitive; he earned his degree in engineering. On the court he was competitive; he helped us win an ACC championship. But as soon as basketball was over, he went right into football. Never played football before, but he was looking for more competition and he found it in football for a year. And then after a few years of not being able to compete physically, he jumped into boxing.”

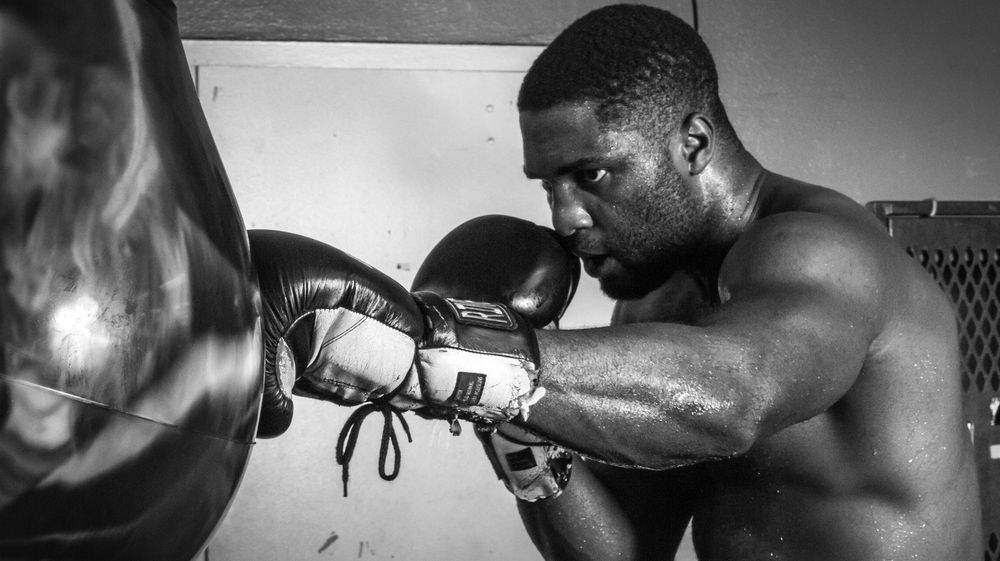

Akpejiori now effectively has two full-time jobs, one at Miami and one as a heavyweight boxer. The time management skills he learned as a student-athlete help him balance the two.

Each day, Akpejiori wakes up between 4:30 and 5 a.m. to go for a run. He then does strength and conditioning work from about 6-8 a.m. After that, he works his day job from 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Once that wraps up, he goes to the boxing gym for about three hours and then returns home at around 8:30 p.m. to wrap up his day and go to sleep.

The roots of Akpejiori’s foray into the boxing world can be traced back to his childhood in his homeland of Nigeria. From the time he was about 11 until he came to the United States at age 17, Akpejiori attended Lumen Christi Secondary School, an all-boys boarding school.

“We fought every day,” he said. “So, I had that natural passion for fighting.”

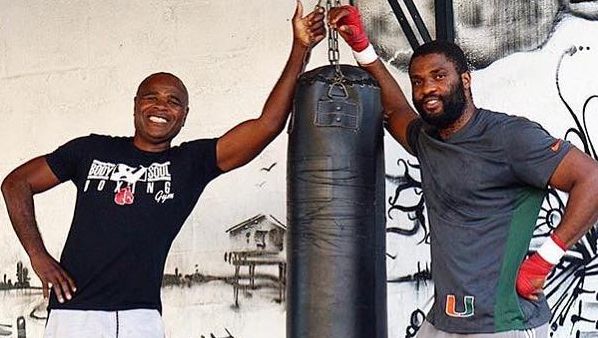

In February 2016, when he decided to pursue the sport more seriously, Akpejiori connected with Dr. Mickey Demos, a former Hurricane boxer in the late 1940s and early 1950s, who is enshrined in the UM Sports Hall of Fame.

After several months of training at Demos’ gym, Akpejiori began fighting in October 2016. He went 13-1 in his amateur career and estimates about 10 of his wins came via knockout.

His initial plan was to retain his amateur status long enough to qualify for and compete in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, but a coach changed his mind, convincing him he was ready to turn professional.

In November 2017, Akpejiori did just that.

He also latched on with a new trainer, Glen Johnson, at that time. Known as the “Road Warrior,” Johnson is a prominent figure in the boxing world, in part because of his 2004 knockout of Roy Jones Jr.

“I didn’t compete for a year just because he wanted to change my style. He didn’t think my style fit me at that time and I didn’t know a lot in terms of the basics of boxing. So, that was the transition for me from the amateurs to the pros,” Akpejiori said. “In the pros now, the only difference is now things are harder. Now you’re a professional. Now, every win matters and every loss matters. You can’t take that out of your record and you get punished for every loss you have. You’re fighting guys who have to feed their families. You’re no longer fighting kids, you’re no longer fighting people just for the love of the sport. Now you’re fighting for money and things are more serious.”

Akpejiori made his professional debut in September 2018 and opened with a knockout. Since then, he has fought six more times.

All of them are wins. All of them are knockouts.

“He’s a big man. He’s tall, he has a good reach and he has an excellent jab,” Johnson said. “He uses his jab wisely and smart and aggressively. And then he can put combinations together right off of that jab. And I think in the heavyweight division, not everybody has that. So, that’s a key weapon for him.”

Both Akpejiori, who had a tryout with the Miami Dolphins in 2015, and Johnson agree the former’s background in various sports—he even played soccer, volleyball and badminton as a kid—has helped him as a competitive boxer.

On the other hand, though, it is also why Akpejiori got a late start in the sport and has quite a bit of ground to make up. Nonetheless, Johnson does see Akpejiori working his way up to an elite level.

“To be a star in any sport, you need to start from a young age, from when you’re eight years old all the way up to whatever. And he would already be a star at his age now [if he did that],” Johnson said. “Obviously, he’s not a star yet. He’s working himself into that because it will take him some [extra] years to get that stardom because he’s in the learning process right now. But I do believe that he will learn because of his effort, his hard-work ethic that he has, his determination and [also because] I believe that I’m a good teacher.”

Akpejiori’s experience in other sports has allowed him to hold a unique perspective on just how difficult boxing is.

While even non-boxers such as Larrañaga think the conditioning demands of boxing are the toughest of any sport, Akpejiori can speak to the extreme tolls boxing takes on you, both physically and emotionally.

“Everything is actually at stake. Your life is at stake, your record is at stake, your money is at stake,” Akpejiori said. “Your friends and family, everybody is holding onto their heart while you’re fighting. That’s the thing about boxing. Boxing is the hardest sport in the world. That’s a fact. The strength and conditioning of boxing alone will make you quit the sport.

“…In basketball, you’re on offense or defense. In boxing, you’re on both at the same time,” Akpejiori continued. “You actually use your offense for defense and you use your defense for offense, if that makes sense. The stakes are much higher in boxing and being that it’s an individual sport, you don’t share the pain with anybody actually. And you actually do share the win with your team, but the pains you [deal with] alone.”

Although still relatively new to the sport, Akpejiori holds lofty aspirations of contending for a world heavyweight title by the end of 2021 and claiming a belt by 2022.

Johnson knows what it takes to fight for a belt and while he is not putting an exact date on that goal for his pupil, he does think Akpejiori can indeed get there and his timeline is not unrealistic.

“I believe he can have the ultimate goal,” Johnson said. “He can go all the way to the top. It’s just a matter of moving smartly and learning along the way.”

There is one particular element of the sport Johnson wants to see Akpejiori improve upon before he deems him ready to fight for a world title.

It is an area of the sport Johnson feels is difficult for all boxers to adjust to, not just Akpejiori. It is, however, particularly important.

“He already has the weapons. I see him use them in the gym and the bags and stuff,” Johnson said. “Now, he just has to translate that into a boxing ring with a live person in front of him that’s trying to throw back punches because that’s one of the parts that most fighters struggle with. You can look good hitting the bags or even shadow boxing or whatever, but when you have live ammo coming back at you, some people get discombobulated because of the thinking and all of the stuff that you have to process quickly.

“…Those are the parts that are the hardest to grasp or to teach or for the student to understand, but he’s learning and he’s understanding that,” Johnson added. “But once he gets that part down, then he’s ready.”

As Akpejiori works his way towards a title fight, he will be doing so right here in South Florida.

Akpejiori does his strength and conditioning work at the same Miami facility Deontay Wilder uses. The two have met multiple times and Akpejiori has received advice from the former world heavyweight champion.

Beyond that, Akpejiori has his next three fights lined up to take place at Miramar Regional Park Amphitheater. The bouts are set for Jan. 23, March 6 and April 17 at the Broward County venue.

Akpejiori hopes he will continue to fight locally well beyond that, as he would like to make this area a prime location for prime clashes in the ring. Not only does he want to see Hurricane fans come out to cheer him on, he also thinks the city is an excellent fit for the sport.

“The goal also is to turn Miami into Las Vegas. We [should not] have to always fly to Las Vegas to have title fights,” Akpejiori said. “We have the arena here. We have the city here. We have the crowd here. We have the aura here in Miami and we can definitely bring [the feel of fights in] Las Vegas to Miami.”

As for Miami the school, Akpejiori looks back upon his time as a Hurricane quite fondly. Despite helping his team sweep the ACC titles in 2012-13, he thinks more about the moments he shared with his teammates than the games they played together.

In fact, he recalls Larrañaga telling the team they would not remember the games. Now 30 years old, Akepjiori understands what his coach meant.

He thinks back on their trip to Hawaii, to a young Tonye Jekiri making everyone laugh and to other fun memories. He has continued to stay in touch with former teammates, even visiting with Shane Larkin when he was in Istanbul.

All in all, Akpejiori, who sports a “U” on his boxing trunks, is grateful for his time as a Hurricane and the path it set him on after graduation.

“My time at UM was great. I had a great five years as a student,” he said. “It was one of the best times of my life and I would never trade it for anything.”

The only thing he has traded is a basketball for boxing gloves. It is a decision his trainer thinks will pay off.

“Raph is a hard worker and he’s very committed and I love working with him,” Johnson said. “I think I have a future champion on my hands.”

Cover photo is courtesy of Will Paul/CES Boxing

Images in boxing gallery slider are courtesy of Autonomic Action