An Olympic Dream Fulfilled: Dario Di Fazio's Story

It would be uncommon for there to be any type of pause in conversation with Dario Di Fazio.

For his divers, co-workers or even the student pool-goers at the University of Miami, the longtime coach is as peppy and talkative as anyone on campus.

So when the halt in dialogue extends past 10 seconds, the magnitude of the topic of conversation is self-evident.

“I’m sorry, bro,” he says, collecting his thoughts. His voice brims with emotion.

The question sounded simple enough: what comes to mind when he thinks of the 1992 Olympics?

The answer, however…well, that’s not so easy. Let’s start at the beginning.

Di Fazio got his start in the sport later than most, but in a fairly common setting – at a local country club, this one in his hometown of Caracas, Venezuela.

“I saw these people spinning around and doing all these tricks off the board, and I said, ‘Damn, I’d really like to try this,’” he said. “There was only one problem – I was not a member of the club.”

Di Fazio was 13 or 14 years old at the time. Thinking outside the box, he decided no one at the club needed to know of his membership status – or lack thereof. He continued to sneak in, multiple days per week for about a year’s time, until he finally got caught by the club’s security.

“I asked if they would just let me use the pool to train, and that I’d pay my fees,” he remembered. “That’s it. I didn’t want to use the tennis courts or the lounge or any of that. They were cool about it. They said, ‘Okay, you can come train during this three-hour block.’ And that’s what I did.

“At the end, they ended up giving me a membership to this place.”

Five years after his first foray into the sport, Di Fazio was competing in his first ever South American Championships, representing his native Venezuela. He’d make several trips to the event, even becoming the first diver to sweep the 1-meter, 3-meter and 10-meter platform in history.

Despite all of his early success, his mind was set on more lofty aspirations.

“I knew if I stayed there, the level [in South America] wasn’t quite where it had to be for me to compete in the Olympics,” Di Fazio said. “That’s why I made decision to move to the United States. I called a friend of mine, Carlos Segui, and if it weren’t for Carlos, I wouldn’t have done the things I’ve done here in the U.S. He opened his doors to me, and said, ‘Come over and I’ll help you out.’”

Segui, who was training with the club program at the University of Miami, told Di Fazio he could live with him if he moved to the U.S. With $1,200 in his pocket and a technical degree in computer science from Venezuela as a fallback option, Di Fazio began the next step in his career.

The duo lived in an apartment in Belle Isle and paid just $350 each month in rent, thanks to one of Segui’s connections in the sport. With one car between them, Segui would drive Di Fazio each day to train.

“It was great. He was and still is a great friend,” Segui said of his time living with Di Fazio. “He’s my little brother from home. He came here, like me, to fulfill a dream.”

Three months after Di Fazio’s arrival stateside, a man by the name of Randy Ableman took over at the helm of both the club program and the Hurricanes varsity diving program.

He had just finished a five-year stint as head diving coach at the University of South Carolina.

“I basically inherited Dario and Carlos and six or seven other postgraduates,” Ableman said. “I went from coaching four or five divers in South Carolina to like 16 college-aged senior athletes, between the club program and the official team.”

Ableman distinctly remembers his new Venezuelan duo, Segui and Di Fazio – especially moments when the necessary focus and effort wasn’t always there.

“He and Carlos had a bit of a fun-loving, laissez-faire attitude,” Ableman said. “In the hot summer and the tight schedule, I remember having to jump them a few times about being late to practice or whatever. It had been a pretty loosely run organization before I got here.”

Segui laughs as he remembers the first few months of Di Fazio training under Ableman’s direction.

“In the beginning, Dario wasn’t used to the life that was here,” he said. “People going here, going there and all we were supposed to do was train, train, train. At the same time, we were young. It was great, always, but there were some difficulties. We were eating like crazy and seeing things we never saw before.”

Ableman had offered Di Fazio a scholarship to Miami, but without a firm enough grasp on the language, he followed Segui’s footsteps instead and elected to enroll at Miami-Dade College. Di Fazio finished at Miami-Dade just before he was set to represent Venezuela at the Olympics, along with his friend Segui, earning a degree in management information systems.

Their final trial for the 1992 Olympics would be the Pan-American Games in Cuba, where the Venezuelan Olympic Committee assured Di Fazio and Segui of their spots, both having achieved remarkable success at the South American Championships.

But they were never sent. Three months before the Olympics, they were told they wouldn’t be going to Barcelona, either.

“That was devastating for me,” Di Fazio said. “Who knows why? That’s what federations used to do all the time. Maybe they were sending more swimmers, maybe it was a money issue. It was never made clear to us. But that was the whole reason I had come here, I had improved tremendously, and now they told me I couldn’t go.”

Despite the enormity of the news, Di Fazio was not yet ready to give in.

Instead of conceding, he wrote a three-page letter that he sent to every major newspaper in Venezuela, explaining his story of being wronged and his clearly earned right to represent Venezuela. Most of the dailies in the country covered the controversial storyline, asking for interviews and follow-up from the committee.

“That letter was pretty spicy,” Di Fazio said with a laugh.

After reconsideration, the Venezuelan Olympic Committee decided upon one final test for Di Fazio; with just three months before the Olympics were set to begin, he would need to earn a medal at an upcoming Grand Prix, in either Vienna, Austria or Bolzano, Italy, before he would earn the right to represent Venezuela.

“Winning a medal at one of those events meant beating the Chinese, beating the Americans, all of these great divers,” Di Fazio said. “I said, ‘You know what? Whatever.’ I knew it was almost impossible. For me to even make the finals in one of those Grand Prix events, for anybody, it would be great.”

In the first of two Grand Prix events in Vienna, Di Fazio dove well and finished eighth.

“When I made the finals of that event, I was on Cloud Nine,” he recalled.

Despite his strong performance, a future trip to Barcelona felt increasingly unlikely by the day.

With little time before his final chance in Bolzano, Di Fazio changed his plans for the next few weeks.

“I had pretty much told myself I was going to do my last meet. As an Italian, with plenty of family there, I had made arrangements to visit my uncle after the meet and spend some time with him,” Di Fazio. “I couldn’t believe I had finished in eighth place in Austria. I was ecstatic. Now they want me to medal in Bolzano? Are you kidding me?”

But Di Fazio upped his game, finishing fifth in the Bolzano preliminaries to earn a place in the finals.

“I’m thinking, ‘Holy cow, this is unbelievable.’”

As he always did during meets, he would spend his time in the locker room between dives.

“I always thought of the competition just as myself, and not anyone else. I had to do six dives and do them right. I never wanted to see what was going on outside,” Di Fazio said. “So after each dive, I left the deck.”

With the meet over, Di Fazio left the locker room and walked towards the pool. He knew what was coming. Given the world-class field in the finals, he had almost certainly finished somewhere outside of a podium finish, his hopes for a trip to Barcelona dashed in the process.

Right?

“I knew I did pretty well, but I had no idea what place I was in,” Di Fazio said.

Everyone was shaking Di Fazio’s hand when he emerged. He didn’t think twice about it, assuming just the standard customs for post-meet interactions, when every diver congratulates one another on a hard-fought event.

Finally, the scoreboard at the end of the pool in Bolzano displayed the final results; Di Fazio had finished third, earning a bronze medal. He broke down in tears upon reading the news, not believing his eyes.

“It was like the movies,” Di Fazio said. “Everybody comes over because they knew the whole backstory. Everybody was hugging me.”

Ableman, who was selected to serve as head coach of the Netherlands for the 1992 Olympics, was on the same deck in Bolzano that day.

“There was a really tough field of divers. The odds of that happening, him getting on the podium, were really small,” Ableman said. “A lot of the really Olympic finalist-level athletes that were there kind of faltered, and he had the meet of his life. And it being in Italy, and him being so proud of his Italian heritage…it was like a fairy tale. He was so happy. He was crying. Just to see him and how proud he was to get to go to the Olympics…seeing the look on his face was something I’ll never forget, really.”

Much like Di Fazio, the Venezuelan Olympic Committee could hardly believe the news. Di Fazio awaited final word, running on the beach every day near his uncle’s place in Italy, trying to keep in shape.

“People thought I was crazy for how much I was running, but I didn’t have any pool to train in, so I just ran all week,” he said.

A week after earning a bronze medal at that Grand Prix in Bolzano, he was given the news he had been waiting for since sneaking into country club pool as a teenager: he would be representing Venezuela in Barcelona at the 1992 Olympics.

“When I got my ticket, I didn’t tell anybody anything,” Di Fazio said. “I showed up at the pool in Barcelona. Randy was there with all these other people. I walked in there and it was magical. It was just…magical.”

It’s there, reminiscing on his first trip to the Olympics, where Di Fazio must stop.

The pause in conversation is lengthy; five seconds turns into 10.

Then 11.

12 seconds of silence have elapsed before Di Fazio can regroup.

It was a dream of 10 years becoming a reality, becoming something that actually happened. It was like being in a dream. When you walk in the Opening Ceremony, I can’t explain it to you. Just an unbelievable sense of accomplishment. Not only that, but I proved to all these people that they were so wrong. I had a vision since I started that I wanted to be at the Olympics. You have to keep dreaming until it happens. Do you know how many times someone told me, ‘No’?”

Dario Di Fazio

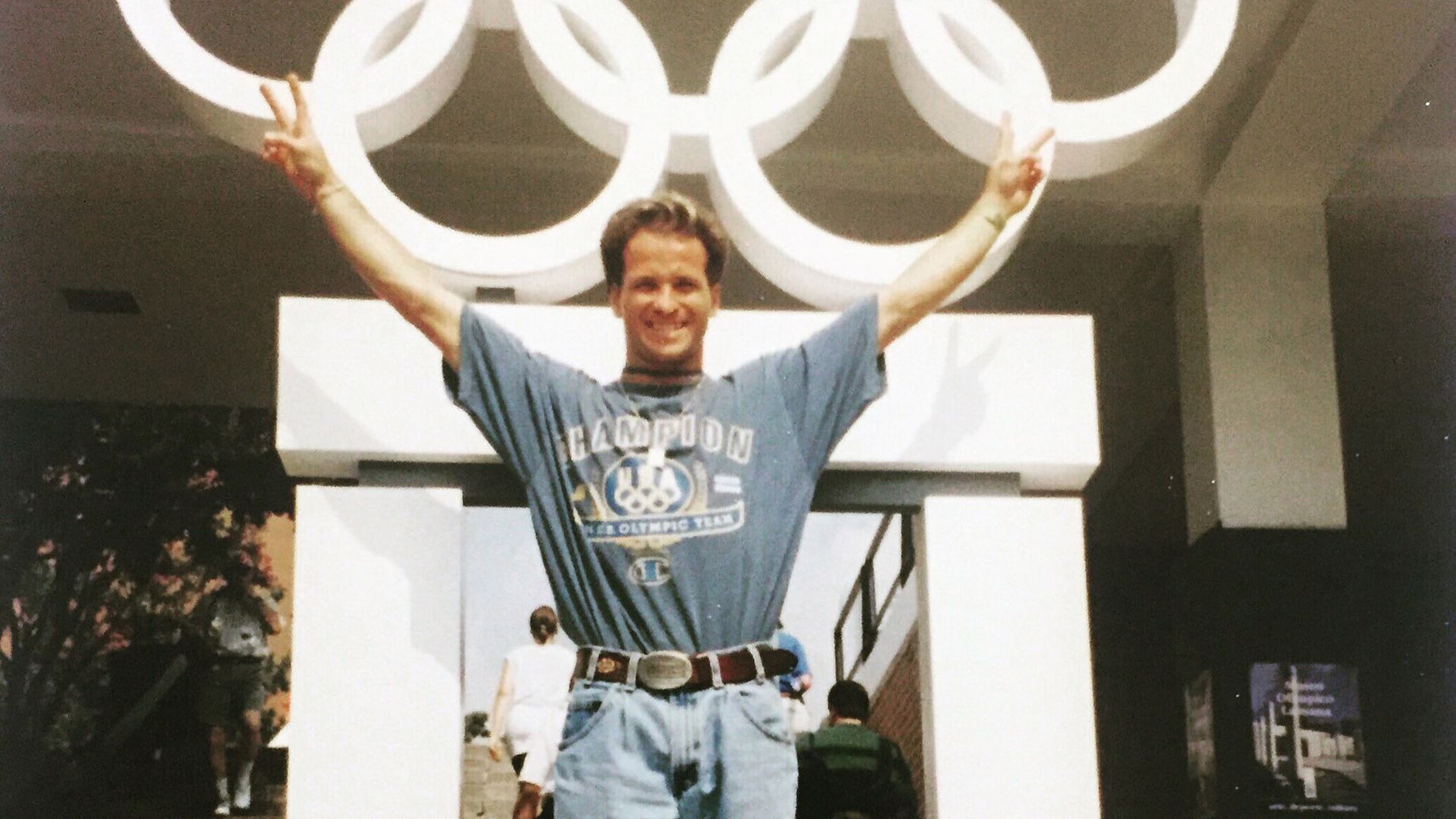

Di Fazio proved the doubters wrong twice, eventually representing Venezuela in the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. Two weeks after he was done diving, and after a conversation with Ableman over dinner, he embarked on a coaching career at Miami that has lasted nearly 30 years.

Though he was reluctant to agree to the position at first, Di Fazio made for an attractive candidate to Ableman.

“He was one of these kids who had to work for everything,” Ableman said. “He got a real late start in the sport. Guys like that tend to make much better coaches. They appreciate what goes into making changes. Everything didn’t come super easy to him.”

Di Fazio, who is Miami’s volunteer coach, heads up the club program while also attending every varsity practice and workout – usually twice per day. He means significantly more than that to Ableman and Miami’s student-athletes.

“We’re a sport where you don’t have a full-time assistant coach,” Ableman said. “Just in the last few years, you’ve been allowed to have a grad assistant. But I’ve basically had another head coach on the deck and it has really been a huge benefit to the program. Not just for me, but the whole legacy of University of Miami Diving has been impacted greatly by Dario being willing to put in that kind of commitment.”

Di Fazio, in turn, said he owes a lot to Ableman. Not only as a coach – where Ableman has a “PhD in diving,” Di Fazio joked – but in his personal life, as well. It was at Ableman’s daughter’s first birthday party that Di Fazio met his wife, Gigi.

They will be married 20 years in September and have a daughter, Mia, and a son, Adrian.

“Most important is the relationship he has with his athletes that makes the difference in him as coach,” Di Fazio said of Ableman. “He has a special bond with each one of them. He gets to adapt to each one of them. Because of that, I think every athlete comes out and tries to give their best, because of their relationship they have with him.

“Randy and I are yin and yang. He has his style, I have mine, but he has let me do my own thing with the divers, to connect. I get to them in a different way than he does and motivate them in different ways.”

For Sam Dorman, who captured a silver medal at the 2016 Rio Olympics and an NCAA national championship at Miami in 2015, Di Fazio’s impact on the program is multifold.

“Dario is all smiles all the time,” Dorman said. “He’s dancing 24-7. You walk into practice, you could be having a tough day, but as soon as Dario walks onto the pool deck…it’s like he demands happiness. He steps on the pool deck and you’re required to be happy. He’s one of those people that, when they walk in the room, instantly people start smiling.”

Much like Ableman, Di Fazio’s ability to connect with his athletes has led to tremendous levels of success on the collegiate and international scene for the Hurricanes.

“He’s extremely good at reading his athletes and understanding the mental side of the sport,” Dorman said. “He’s very good at seeing those emotions go up and down, and managing that when you’re diving. He teaches you how to control those emotions for the ultimate goal of competing.”

Dorman, entering his second year as a student in Miami’s MBA program, said Di Fazio has played a pivotal role in his life since arriving to Coral Gables as a freshman in 2010.

“The guy is like a father to me,” Dorman said. “I still go to his house and have dinner. Sharing the experiences together and being able to look back and have those conversations and share memories and swap stories, it’s so much fun.”

To Segui, Di Fazio is the same person as he was when he arrived to that run-down apartment in Belle Isle at the age of 22, with faint hopes of making the Olympics.

“I love him dearly, with all my heart,” Segui said. “He is a very special person. He goes with whatever is on his mind, and he gets there. He loves to fight for what he thinks is right…I’m super proud of him and what he accomplished.”

To Ableman, it’s Di Fazio’s passion that makes him stand out above the rest.

“He’s got this heart and this love of the program that if someone is screwing up, he takes it as a personal offense,” Ableman said. “He just jumps right out. He’s a lot of things that I’m not, and that’s why it has been such a good mix. He takes a lot of personal pride in being a part of the program and helping these kids develop.

“These kids have high goals and there’s no pro contract at the end of it. We’re putting in a lot of extra work and care with each of them to get them to their potential, and we’re doing it for the kids. He gets that. We’re very fortunate. He’s irreplaceable.”

While reminiscing on his Olympic dreams proved emotional, and despite his love for story-telling, make no mistake about it – Di Fazio is always thinking ahead.

For one conversation, though, he focuses on what has been accomplished – as unnatural as it may feel.

“It’s funny. Here we are, coaching Olympians and winning medals and we are already thinking what we’re going to do next,” he said. “You don’t sit down and think about what you’re worth. If some people might remember me, I hope it’s that I’ve helped people to grow, not only in the diving aspect, but one of my goals is to bring these people from kids to becoming men and women, and to be positive individuals in society, with a high sense of self-esteem. To accomplish things beyond their diving career.

“That’s what I’d want people to think about when they think of me – someone who has helped them that way. Not only in the technical aspect and keeping their diving dreams alive, but pushing them through when they’re going to hard times. I enjoy that.”