Coaching Continuity

CORAL GABLES, Fla. – During his first Division I head-coaching stint, at Bowling Green, Jim Larrañaga remembers hiring a new assistant or two on a nearly annual basis.

After 11 years leading the Falcons, Larrañaga left for George Mason in 1997 and then went to the University of Miami in 2011. Since bringing on his initial staff in Fairfax, Va., only eight times in 23 offseasons has he hired even one assistant.

In fact, just 11 people have held an assistant coaching job under Larrañaga over the past 23 years. Few top-level coaches have been able to maintain the same type of stability on their staff that Larrañaga has.

“When everybody knows what I believe in, everybody’s following in that same direction,” Larrañaga said. “We don’t have a lot of poor communications between the staff and the players. If you talk to a player and the players are confused by what you mean, there’s a real problem with that.”

Now entering his 10th year as the head coach of the Hurricanes, Larrañaga presents a specific example to demonstrate the pitfalls that arise without staff consistency.

During his time as an assistant coach at Virginia, Larrañaga yelled to a player to deny, while a fellow assistant screamed for him to get in the lane. The player came over to the bench and asked if he was supposed to deny the pass or to get in the paint, thinking the other coach meant the three-second key.

Larrañaga’s colleague, however, also meant the passing lane, but the difference in lingo puzzled their pupil.

“Once the coaches get on board with the same terminology, then it’s much easier for the players to listen and learn and execute,” Larrañaga said. “So, that’s why it’s so important to have good continuity on your staff.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

For Miami’s three assistants, the upcoming 2020-21 campaign will serve as their 38th combined season with Larrañaga. Only North Carolina’s staff, entering its 43rd cumulative year under Roy Williams, has a higher number in the ACC.

Chris Caputo is going into his 19th year on staff for Larrañaga, the only coach he has worked for. Bill Courtney will be in his second season at Miami, but his 11th with Larrañaga, as they spent nine years together previously. Adam Fisher is headed into his eighth campaign under Larrañaga.

“People don’t realize how hard the coaching staff works. When you have a group that has been together for such a long time, everything becomes more fluid,” Miami redshirt senior center Rodney Miller, Jr., said. “You know what people like and what they don’t like, how to react and handle certain situations. I feel like having consistency in the coaching staff has played a huge part in my development here at UM.”

Even Larrañaga’s coaching support staff has great continuity, further helping with that steady message. Director of operations Lamont Franklin is entering his fourth year with the Hurricanes, while assistant director of operations Jeff Dyer is heading into his sixth, across two stops.

While the stability certainly helps with X’s and O’s, terminology and play calls, it does much more than that. It allows the players to form strong bonds with their coaches off the court.

“Players need their coaches in college basketball, it’s just a thing. We spend so much time with those guys,” Courtney said. “They need you in so many different ways and they have to trust you. It’s hard to build trust if the deck is constantly being shuffled. So, because you have continuity, guys feel comfortable when they go to you, whether it be something about basketball, whether it be something about school, whether it be something in their personal lives. I think that trust in their coaches really helps the players.”

Miller, who put his faith in the staff when he took a redshirt year in 2018-19 and has since seen that risk pay off, also mentioned positive off-court communication as a benefit of coach continuity.

The theme of trust is one echoed by Larrañaga, whose 660 victories make him one of the 40 winningest coaches of anyone with Division I experience.

“The whole key to getting a player to trust you is to develop a relationship, on the court and off the court,” Larrañaga said. “Because my players at Miami have spent so much time with my assistants, there is a sincere trust. Even with their parents, there’s very good communication.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

On the rare occasion he sets out to hire a new coach, Larrañaga has three basic attributes he looks for. First, he wants to find people smarter than him. Second, he seeks individuals who will serve as good role models for his players, both on and off the court. Lastly, he wants coaches with well-rounded abilities across the various aspects of the job.

It is evident that Larrañaga has an eye for coaching talent, as seven of his 11 assistants over the past 23 years have gone on to earn head coaching jobs.

Courtney served in the top spot at Cornell from 2010-16. Michael Huger and Eric Konkol have been at Bowling Green and Louisiana Tech, respectively, since 2015. Derek Kellogg was UMass’ head coach from 2008-17 and then took the job at LIU, where he has been since 2017. Mike Gillian held the reigns at Longwood from 2003-13, Scott Cherry was at High Point from 2009-18 and James Johnson led Virginia Tech from 2012-14.

“When everybody knows what I believe in, everybody’s following in that same direction. We don’t have a lot of poor communications between the staff and the players. If you talk to a player and the players are confused by what you mean, there’s a real problem with that.” -Jim Larrañaga

Four of those seven individuals have served multiple spells under Larrañaga. Courtney is, of course, the most recent example, returning to Larrañaga’s staff 14 years after departing.

Cherry went to Tennessee Tech for one year, 2002-03, before coming right back to George Mason. Konkol left the coaching industry for two years, 2005-07, and then returned to Fairfax, Va. Johnson departed George Mason in 2007 and came to Miami eight years later, serving in a non-coaching role, as the director of basketball operations, from 2015-17.

Caputo, Larrañaga’s longest-tenured assistant, has worked with every one of those coaches and feels their returns say a lot.

“I think that speaks to Coach L’s loyalty, but also to the working environment. I don’t think people understand that a lot of times in our business, people are just trying to do a good job and get out of the place they’re in because they’re unhappy,” Caputo said. “I think the working environment that Coach creates, while it’s demanding, I actually think it’s very similar to how it is with the players. It’s demanding, but it’s not demeaning; it’s fair. You know you’re working for someone who has, I think, first, the players’ best interests. I think that’s so important to good people, to know that the guy you work for is really looking out for the players.”

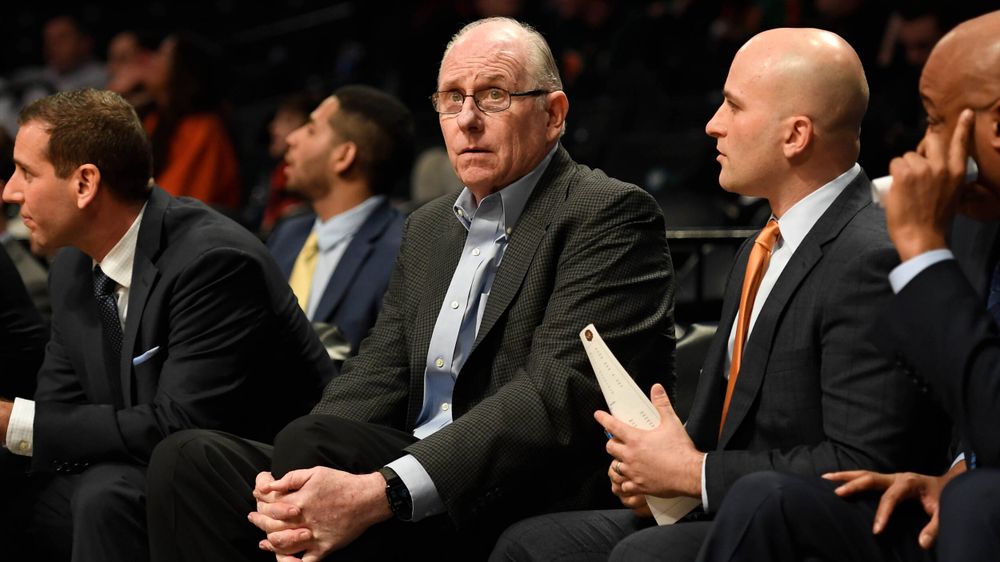

Huger, Konkol, Larrañaga and Caputo in 2010-11, their final season at George Mason

Courtney had the longest gap between his years with Larrañaga, but the transition back was seamless when he got the job at Miami 13 months ago.

The strong relationship they maintained while Courtney worked elsewhere assuredly helped, but the program’s overarching pillars, regardless of the name on the front of jersey, were also quite familiar.

“Through the years, from the commitments to the affirmations, all those things were the things that 20-plus years ago . . . . we did at Bowling Green and George Mason,” Courtney shared. “It’s exactly the same the way he runs the program and the expectations and the commitment that he asks of the players and himself, all of that stuff. ‘Attitude, commitment and class’ has been around for a very long time.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Of the 45 assistant coaches in the ACC, only three have worked with their current boss longer than Caputo has for Larrañaga.

They first met over 20 years ago at an all-star game in Connecticut. Caputo, then junior guard at Westfield (Mass.) State University, had a connection to Larrañaga and used it to present himself.

Both men attended Archbishop Molloy High School in Bronx, N.Y., where they played for the legendary Jack Curran, the winningest coach in state history in both basketball and baseball.

“He came up and introduced himself, said he went to Molloy, he recognized me and he told me he wanted to get into coaching,” Larrañaga recalled. “I gave him my business card and said, ‘Stay in touch.’ So, he started emailing me . . . and for the next year and a half, I would hear from Chris Caputo four, five times a week.”

Near the end of Caputo’s college tenure in 2002, it was Larrañaga who sent an email that ended up changing the former’s life.

“I got an email from Coach basically saying, ‘Hey, man. I have an assistant job open. I need you to apply for it.’ I’m thinking to myself, ‘Man, this is really easy. You just apply for the job. The head coach of a successful Division I school just emails a college senior and says, hey, apply for this job,’” Caputo jokingly recalled. “I’m thinking, ‘Wow, I don’t know what people are talking about, this getting into coaching thing is not that hard.’ Then, when I finally talked to Coach on the phone he was like, ‘Look, you’re not getting this job, but I need you to be on the list of people that apply and if I want to talk to you about an opportunity, I need you to be in the system.’”

Larrañaga hired the more experienced Konkol for the assistant coaching role, but wanted Caputo around his program and came up with a way to make that happen.

In an era before schools had large support staffs littered with operations and administrative roles, Larrañaga presented Caputo with the one thing he could.

“I liked Chris a lot,” Larrañaga said. “So, I told him, ‘I don’t have a job for you, but if you want to volunteer and just be around the staff and learn as much as you can, you’ll have to finance yourself. There’s no salary.’ He said he would do that.”

For about three months after taking their respective jobs, Caputo, then 22, and Konkol, then 26, actually lived with Larrañaga and his wife, Liz.

Caputo, with the self-administered title of administrative assistant/video coordinator, quickly began to show his worth and, according to his boss, even worked 19-hour days.

“He wrote his own job description, whatever he was comfortable doing,” Larrañaga said. “He did phone calls to high school coaches to talk about camp. He talked to AAU coaches. He worked the [Eastern Invitational Basketball Camp]. He did video.

“No one worked harder than him,” Larrañaga added. “No one was better prepared.”

After Caputo’s first year at George Mason, Gillian got the head job at Longwood. Larrañaga told Caputo he did excellent work, but was not ready to move him up just yet, instead re-hiring Cherry after his one year at Tennessee Tech.

“I think the working environment that Coach creates, while it’s demanding, I actually think it’s very similar to how it is with the players. It’s demanding, but it’s not demeaning; it’s fair. You know you’re working for someone who has, I think, first, the players’ best interests. I think that’s so important to good people, to know that the guy you work for is really looking out for the players.” -Chris Caputo

Meanwhile, Gillian, impressed by what he saw during their one campaign together, offered Caputo an assistant position at his new school, 150 miles southwest in Virginia. However, Caputo was not sure he should take it.

“I’m either going to go to Longwood to be on the road full-time, which would’ve been a pretty good job, [or stay at George Mason],” Caputo said. “But in my heart of hearts, I also kind of felt like, ‘Look, I’m at a pretty high level of Division I right now. I think we’ve got a good team. Nobody knows who I am. Longwood is really a hard job . . . I’m just getting my bearings, starting to develop a little bit of a network of people being in the D.C. area, working camp, all this stuff.’”

Caputo explained the situation to Larrañaga, who asked how much the Longwood job offered. Caputo told him it was roughly $30,000, plus a car.

“I remember he said, ‘Well, you already have a car.’ So, I’m like, ‘Good point,’” Caputo chuckled. “He [said to me], ‘What if I pay you $500 a month?’ I’m like, ‘I think I’d stay.’”

He stayed indeed and Larrañaga used money generated from camp to pay Caputo out of his own pocket. The following season he doubled Caputo’s pay, via those camp earnings, and gave him $1,000 a month.

After the 2004-05 campaign, Konkol moved to Minnesota and took a job outside of basketball. That opened a full-time job, which Larrañaga offered to Caputo and he accepted.

In his first year as an assistant coach, Caputo helped lead the Patriots on the greatest Cinderella run in college basketball history, as George Mason defeated Michigan State, North Carolina, Wichita State and UConn, en route to the 2006 Final Four.

Larrañaga, Caputo, Johnson, Cherry and the Patriots celebrate advancing to the 2006 Final Four

Five years later, Caputo, along with Huger and Konkol, retained their spots as assistant coaches when Larrañaga took the Miami job. In 2015, Caputo earned a promotion to his current status as associate head coach.

“It’s no secret I owe my career to Coach, really every step of the way in terms of, first, the initial belief to even have me come down, and then the belief and the trust in elevating me throughout my time with him,” Caputo said. “In a lot ways, he’s a father-figure to me . . . [and he is] a mentor. I’ve learned so much not only about basketball, but the business. I’m sure at first I thought I knew everything; he quickly put me in my place. You gain some humility there. Hopefully I’ve been able to add value to warrant and thank him for the opportunities that he’s given me. The loyalty that he’s shown me, hopefully I’ve done a good job reciprocating that.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Much like Caputo, Fisher also had the chance to leave a non-coaching role under Larrañaga for an assistant job elsewhere with a former colleague.

A Jamison, Pa., native, Fisher came to Miami in 2013, just after the Hurricanes swept the ACC titles, as the director of operations. He left his home state and his alma mater, Penn State, where he was the director of player development, to come to Coral Gables.

“You just look at Coach L’s track record. Everybody in the business has the highest regard for him,” Fisher said of why he wanted to work at Miami. “He . . . had that staff for several years together and those guys were all hot names to become head coaches. Part of that lure was, he must be doing a great job of teaching his staff to be head coaches because those guys’ names were just popping up for jobs everywhere. The lure was just Coach L, what he’s done, his ability to win, graduate players. All that stuff just was something that I really wanted to learn under him.”

Fisher was so enthused about the possibility of working at Miami that he used a unique idea to display his interest to Larrañaga.

Over the course of two days, Fisher used orange and green spray-paint on a pair of shoes until they looked just right. Then, he shipped them to the man he hoped to work for.

In it, he included a note that read, “Coach L, I’m two feet in to be a Hurricane. I didn’t have any green and orange shoes, so I made my own. I’ll always find a way to get the job done for you.”

Larrañaga hired Fisher and was impressed by the newcomer’s abilities in an operations role despite his interest in eventually becoming a full-time coach.

“He was very, very intelligent. He was very hard-working. He was a great communicator,” Larrañaga recalled. “He developed great relationships with our players, with our fan base, with some of my friends. He really created an image of himself that was very recognizable, not only by me, but by others.”

In 2015, when Huger left Miami for the head job at Bowling Green, where he played for Larrañaga from 1989-93, he presented Fisher with an opportunity to join him as an assistant coach.

“You just look at Coach L’s track record. Everybody in the business has the highest regard for him." -Adam Fisher

The Falcons were coming off a 21-win season and Fisher had familiarity with Huger from their two years working together. However, much like Caputo 12 years earlier, Fisher was not sure leaving Larrañaga was the right choice.

“Coach Huger is one of my closest friends; he was at my wedding,” Fisher said. “That was a tough decision, but Coach called me one day, I think it was a Sunday, and just said, ‘I’d like you to stay, but it’s going to be in the same role.’ Quite frankly, I just trusted Coach and I said that to coach Huger. I said, ‘Hey, this is a guy who believed in me, hired me and I’m going to trust him with my career path.’”

That trust quickly paid off, as Fisher soon became the fifth first-time assistant coach Larrañaga hired since beginning his George Mason tenure.

“I told him if Eric or Chris left, he’d take their spot. Eric left two weeks later [for Louisiana Tech] and I elevated ‘Fish,’” Larrañaga said. “The first thing he did was get me on the phone with Lonnie Walker.”

Huger, however, did bring on three other people he worked with at Miami to various roles at Bowling Green. One year later, he hired Dyer, who completed his two-year graduate assistantship at Miami in 2016, as his video coordinator.

The next offseason, Dyer returned to Miami in his current role, further helping solidify Miami’s staff continuity. That stability extending beyond the coaches and into the support group is vital in Fisher’s mind.

“I think the more you have people together, the more you get to know each other. This is going to go on year eight in a row for coach Caputo and I, and Coach L, which I think is really helpful,” Fisher said. “A guy like ‘BC,’ even though I’ve only worked with a year, he’s become one of my closest friends. We’re so close, but I’ve gotten to know him ever since I got the job here because Coach L always would tell stories about ‘BC.’ So, I’ve reached out to him when he was at other spots and when [I would] see him on the road when he was with other teams.

“And then you have guys like Lamont Franklin [and, before him, James Johnson], guys that have been around Coach L, been around the business for a while. Good family guy in Lamont,” Fisher continued. “Jeff Dyer, obviously, he was a GA at Miami and him and I worked really closely together when he was here, so the chance to bring him back was really important. I think he’s a huge part of the staff continuity, too.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Courtney, known by those around the Miami program as ‘BC,’ has the longest-standing relationship with Larrañaga of any of his assistants.

In 1996, entering what proved to be his final year at Bowling Green, Larrañaga hired the 26-year-old Courtney, who then had just one year of college coaching experience at American. They then went to George Mason and spent another eight years together.

Courtney’s bond with the Larrañaga family extends beyond Jim, as he is also a close friend of the latter’s son, Jay, now an assistant coach for the Boston Celtics. Courtney even hired Jay to be his assistant at Cornell.

A Division I coaching veteran with a quarter-century of such experience, Courtney credits much of what he has learned to the man who hired him two-dozen years ago.

“It’s almost like family. It’s even more than friendship, to me. He’s been a great mentor to me, on and off the floor,” Courtney said. “It started back when I was 26 years old. Things at the time, when you’re 26, you don’t think. You think you know everything, but he would tell me things and a year or two later I’d say, ‘Oh man, I remember Coach L used to say that.’ That happened so many times throughout my life, more than just the basketball court, but everything in life, he’s taught me so much.”

On the other hand, Larrañaga has also taken helpful advice from Courtney, especially in one specific area of the job. Beyond that, though, much like Courtney, Larrañaga sees their connection as one that extends beyond the hardwood.

“We’ve been best friends for 25 years. When we were at Bowling Green, we traveled constantly together. When we were at George Mason, we traveled constantly together,” Larrañaga shared. “He identified recruits and took me to them, got me on the phone with them. Bill was a relentless recruiter. He had more insight into recruiting and he really helped me. He helped me improve as a recruiter. It was [so much] fun traveling around with him and we have a lot of great stories.”

Unlike Caputo and Fisher, who have only served as assistant coaches for one person, Courtney has worked for four others.

There is an appeal, though, in serving on Larrañaga’s staff that made him interested in doing so 14 years after leaving it.

“Well, he’s one of the best coaches in the history of college basketball. The numbers speak for themselves of what he’s done,” Courtney said. “[He has not] done it at name-brand schools, he’s had to go and build programs wherever he’s been. He hasn’t done it at so-called, quote-unquote ‘basketball schools.’ When we arrived at George Mason, they were coming off four straight last-place finishes and seven straight losing seasons, I think it was. When you get a chance to be around someone who has built programs and learn and get to see that from the ground level—I’ve always been able to see it right from the ground level in how he’s done it—you take everything with you.”

Courtney’s return to Larrañaga’s staff has been quite smooth. He also proved his dogged recruiting chops once again, helping lead Miami’s successful effort to sign top-35 recruit Earl Timberlake, who hails from Washington, D.C., just 20 minutes north of Courtney’s hometown, Alexandria, Va.

“Through the years, from the commitments to the affirmations, all those things were the things that 20-plus years ago . . . . we did at Bowling Green and George Mason. It’s exactly the same the way he runs the program and the expectations and the commitment that he asks of the players and himself, all of that stuff. ‘Attitude, commitment and class’ has been around for a very long time.” -Bill Courtney

His addition to the staff came at a welcome time, as 2019 was just the second time in the last 23 years Larrañaga hired an assistant coach in a second straight offseason. Bringing back someone with profound familiarity made the change especially smooth.

“The biggest thing is, we’re all older,” Courtney noted with a laugh. “So, it wasn’t a [difficult] adjustment, especially partly because even when I wasn’t working for him, we were always still in touch and still good friends.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Some aspects of their professional journeys are similar, while others are different. All of Miami’s assistant coaches, though, have taken a path that led them to form one of the most stable staffs at the Power Five level.

While the familiarity that has created certainly benefits Miami in the present, their paths have helped shape each of them as individuals.

“I think I’ve learned that you’re a teacher first. He’s always teaching, whether it be life or basketball. I think what he does so well is he’s a great listener. He hears our players,” Fisher said. “His ability to adapt, whether that’s in-game to make halftime adjustments or that’s how to handle an academic situation, whatever it may be; Coach L listens and then makes great, sound decisions. A lot of it is probably based off his experiences, which he passes down to us. I think he gives his staff the opportunity to grow, just like the players.”

Larrañaga has clearly created an environment that players want to be a part of, evidenced both by his stellar recruiting classes and the fact that just one Hurricane in the last four seasons has transferred to another school.

“The whole key to getting a player to trust you is to develop a relationship, on the court and off the court. Because my players at Miami have spent so much time with my assistants, there is a sincere trust. Even with their parents, there’s very good communication.” -Jim Larrañaga

At the same time, Larrañaga has also developed an atmosphere that coaches want to be part of and that is what has allowed the staff to remain so constant.

“You feel like this guy is not all about himself, he’s got empathy, he thinks about other people. We’re in a very demanding, cutthroat, hard business to be in and so it’s not like every day is an easy day, but I think if you know that the North Star, the leader, is about all the right things, I think it creates a great working environment,” Caputo said. “In any great organization . . . continuity is so important. I just think that there is such a thing as corporate knowledge, that there is such a thing as understanding a culture and implementing a culture, and it just takes time to do those things. Too often in coaching, people are just in and out; they can’t really make much of an impact.”

Larrañaga and his small group of assistants have undoubtedly made an impact and the 37th-year head coach’s dazzling resume, as Courtney mentioned, speaks for itself.

Caputo alone has been by his boss’ side for seven NCAA Tournament berths, three Sweet 16 trips and a Final Four appearance, as well as four conference regular season titles and four league tournament crowns.

“We owe it all to Coach L,” Caputo said, “because his success and stability have created success and stability for us.”

His staff members are certainly grateful for him, but through relationships built over the course of three decades, that feeling is mutual.

“I’ve got a great staff. They’re great guys,” Larrañaga said. “They get along great together. To me, they’re like family.”