Inspired by a Remarkable Legacy

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story is part of our Together 4 Her series. Launched in conjunction with the 50th anniversary of Title IX legislation, Together 4 Her is a year-round initiative by UM Athletics that showcases accomplishments of women from around the university while supporting gender equality on and off the field of play. For more information click here.

CORAL GABLES, Fla. – The photo sits prominently in her office, within view of her desk and her door, a constant reminder of the woman who inspires her and the values that drive her.

Day in and day out, Shirelle Jackson – Miami’s Executive Associate Athletic Director for Student-Athlete Development – seeks to impact the lives of countless Hurricanes.

From mentoring sessions and resume workshops, to encouraging community engagement and beyond, Jackson’s mission is to ensure Miami’s student-athletes are ready to handle the challenges that await them after graduation.

And in all the work she does, Jackson draws inspiration from the woman in the center of the photo in her office – her grandmother, Hattie Turner Palmer.

In the image, Palmer is joined by her parents and her husband. She’s smiling, wearing a cap and gown and holds in her hands the physical education degree she earned from Tuskegee University, a degree that allowed her to become a teacher after her graduation.

Palmer, who ran track and played basketball at Tuskegee, earned that degree in 1946, long before the groundbreaking legislation known as Title IX helped pave the way for millions of young American women to compete in college athletics around the country.

But by competing at Tuskegee, Palmer was able to earn stipends that helped pay her way through school. As Jackson notes, though, those stipends were far cries from the athletic scholarships earned by student-athletes today.

They weren’t guaranteed annually. They covered only the season in which one competed. And that meant Palmer – who arrived at Tuskegee hoping to merely compete as a track student-athlete while pursuing her degree – had to get creative and learn other sports.

For Palmer, it was a journey of uncertainty that played out far from her Ohio home. And that is why Jackson keeps her grandmother’s photo in her office.

“That graduation picture really serves as motivation for me. I really don’t have bad days, compared to what she went through,” Jackson said. “She chose to leave home. She was the first to graduate from high school in her family…She decided she did not want to be a domestic. It just was not in her to do that. The only thing she knew was that Tuskegee and Tennessee State had track teams and Black women were playing sports at those two institutions, so she got on a bus and found herself in Tuskegee.

“I think about the privileges I have and how I was born into a family that really values education and that really started with Hattie…To leave her family to go to college and play sports, I mean, women weren’t playing sports. Women weren’t going to college in the late 30s, early 40s…The fact my grandmother decided to go and compete and finish, I take great pride in that.”

That pride, Jackson says, carries over into her work with Miami’s student-athletes, many of whom have asked Jackson about the woman in the framed black-and-white photo.

And Jackson is happy to answer every question, sharing with the Hurricanes who ask why the image is so important to her and hopefully, inspire them the same way Palmer inspires her.

“I want to do everything I can to remind our student-athletes about all the opportunities they have, our men and our women. I think it’s lost on them, sometimes, the fight that happened before them,” Jackson said. “The picture, for me, is a reminder. When I go ‘Oh my gosh, there’s so much going on. I’m so busy’ and I get bogged down, I think [about how] I’m not having to worry about do I have to drink out of a colored water fountain or not, or when I was an undergrad, was I going to have a uniform or how I was going to travel. Those things were afforded to me not only because of my grandmother, but all of those women who paved the way for all of us up until 1972. And then, more men and women fought to make sure that federal law went into place.

“So, when I think about all of those pieces and I think about our current student-athletes population, I feel like it’s a bridge of the past, present and future…I think about that narrative of not allowing someone else to define you. My grandmother, by everything she was being told and everything she saw, was told ‘You’re supposed to be a domestic.’ She said ‘I’m not going to be. I’m going to be a college student-athlete.’”

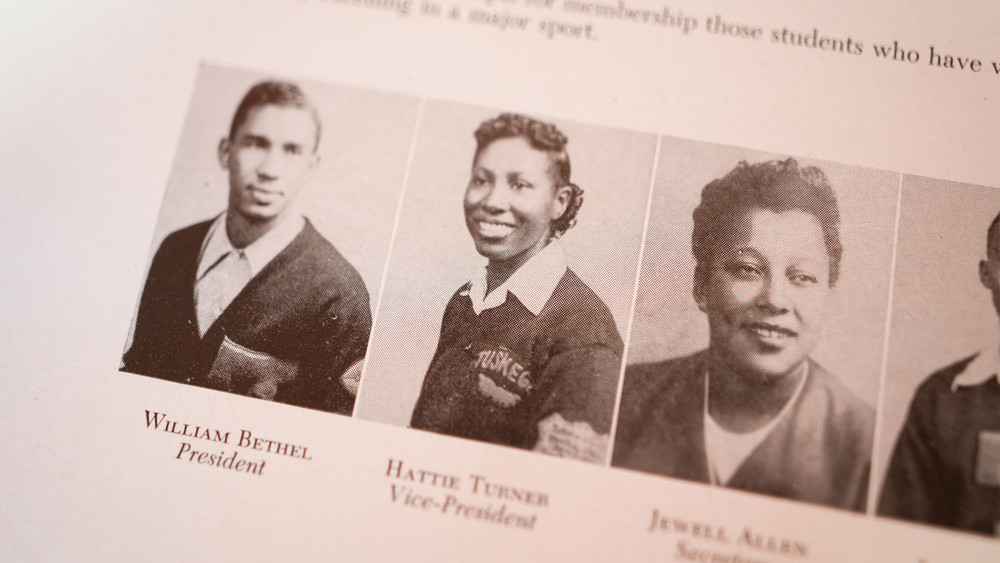

During her time at Tuskegee, Hattie Turner Palmer was in several campus leadership groups, including the school's "T Club" for student-athletes. (Photo courtesy Shirelle Jackson)

But Palmer’s influence extends far beyond the work Jackson does at Miami.

It has carried over into nearly every facet of Jackson’s life.

She, too, was a track and field student-athlete, competing at Bowling Green, where she earned her undergraduate degree.

Her sons, Justin and Jordan, also competed collegiately, Justin on the track and field team at Nova Southeastern University and Jordan on the basketball team at FAMU, an HBCU like the one his great-grandmother attended.

And whether it was on display during her days as a fashion buyer right out of college or as an academic advisor later in her career, her work ethic and drive to help others, Jackson says, come straight from Palmer.

After her time as a teacher, Palmer co-owned and operated a family driving school that taught Black children in Cincinnati how to stay safe on the roads. She and her husband, Coleridge, also co-owned a flower shop, Palmer’s Florist, which addressed a different kind of need in their community.

“I do this work because I enjoy the work. I don’t do the work for the accolades. I don’t do the work to see who’s paying attention. I do the work because all these years later, I still want to help people,” Jackson said. “It goes back to the core of wanting to help people. That’s a core memory of my grandparents. My grandmother, when she got out [of teaching], still wanted to help people. ‘Oh my gosh, no one’s teaching these Black children to drive? We will. We can’t order flowers from anywhere in the Cincinnati area? Well, we’re going to create that.’ I feel like I got all of that from them.”

Shirelle Jackson, Miami's Executive Associate Athletic Director for Student-Athlete Development, in her office. (Jacob Brown, Miami Athletics)

While her grandparents have inspired her, there’s no doubt Jackson herself been a motivating force to the students and student-athletes she has mentored during her career at Miami, first as an academic advisor in the College of Arts and Sciences and now, in athletics.

Shortly after making the move to Miami’s athletic department in 2014 and creating the Office of Student-Athlete Development, Jackson was approached by a member of the Hurricanes swim team who asked how she’d built her career.

Her goal? Help student-athletes in much the same way Jackson had helped her and her peers.

Today, that swimmer – Jessica Hurley – works with Jackson doing exactly that.

“I legitimately walked into her office and said ‘I want to be you one day. Your job is to change the lives of others. You make people better. I want to do that. It’s incredible. It’s amazing,’” said Hurley, who now serves as an assistant director for student-athlete development. “She has completely changed my life. I would not be in this career without her. There’s no doubt I would not be in this career without her. You can see her passion. And her ability to relate to each student-athlete…she helps everybody become a better person and very positively impacts every person she meets.”

For Hurley, the inspiration was Jackson. And for Jackson, it was, and continues to be, Palmer.